SMART AT A CROSSROADS - Marin Grand Jury ( June 2023)

SMART’s Threats and Challenges

The primary “threat” to SMART is its dependency on the locally

imposed sales tax. As recognized in its own SWOT analysis, a well-funded and

organized opposition to the sales tax could very likely cause the service to

end.

Lack of ridership not only contributes to public questioning of

the system’s value, but it also means less revenue. SMART cannot survive on

ridership revenue alone. Rather, it requires a public subsidy to continue

operating. This is not atypical; all the largest public transit systems in the

San Francisco Bay Area are financed by public subsidies. The question is how

much of a subsidy will voters accept.

An operation such as SMART has significant fixed costs to

operate. This means that regardless of the number of riders or the fares that it

charges its riders, SMART’s operating expenses do not vary significantly over

time. As demonstrated in Table 1 below, SMART’s annual operating expenses (which

exclude capital expenditures and debt service) have remained about $27 million

since 2019. But in the past four years revenue from riders approached $4 million

just once.

The data speaks for itself and the lesson is clear: SMART cannot

survive just from its farebox. It requires some form of public subsidy. SMART’s

primary source of operating revenue is and has always been the local sales tax.

In FY 2022, sales tax receipts were $49 million compared to $1.2 million

obtained from the farebox. The current FY 23 budget forecasts $51.6 million in

sales tax collections.

As demonstrated in Table 1, SMART’s ridership, and therefore its

farebox revenues, declined precipitously during the pandemic and have yet to

recover.38

SMART’s farebox recovery ratio, i.e., the amount received by paying customers

relative to operating costs,

dropped from 15 percent in 2019 to as low as 3 percent in 2021, and 5 percent in

2022.

The end result is that the sales tax has subsidized SMART ridership, ranging

from $32 to $75 per ride, with a high of $196 in 2021.

dropped from 9 percent in 2019

to as low as 2 percent in 2021, and

3 percent in 2022.

The end result is that the sales tax has subsidized SMART ridership,

$128 in 2019, $168

in 2020, $518 in 2021, $240 in 2022 per

ROUNDTRIP.

| |

Non-Capital Expenditures including Debt

Service $ |

Subsidy per Boarding $'s |

Subsidy per ROUNDTRIP $'s |

Farebox Recovery |

Farebox

Revenue $ |

Boardings |

|

2017 |

33,710,422 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2018 |

40,704,021 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2019 |

46,089,431 |

64 |

128 |

9% |

4,094,540 |

716,847 |

|

2020 |

47,767,685 |

84 |

168 |

6% |

3,090,457 |

567,103 |

|

2021 |

34,924,294 |

284 |

568 |

2% |

706,938 |

122,849 |

|

2022 |

42,526,001 |

120 |

240 |

3% |

1,283,112 |

354,291 |

|

2023 |

46,201,183 |

|

139 |

|

1,800,747 |

640,099 |

|

2024 |

50,345,042 |

|

*113 |

|

2,192,253 |

851,115 |

2022 SOURCE page 79

2024 SOURCE page 79 Links to all

Financials

*But boardings include all the FREE youth and

senior riders so Subsidy of the other riders is far greater !

Grand Jury FINDINGS

- F1. SMART is heavily dependent on revenue from voter approved Marin and

Sonoma County sales taxes for funding its operations.

- F2. SMART has never attained the ridership levels that it promised in

2008.

- F3. SMART’s past inability to be open and transparent about decision

making and operations contributed to the erosion of public confidence leading

to the defeat of the Measure I sales tax extension in 2020.

- F4. SMART will likely be forced to discontinue services if Marin and

Sonoma County voters do not approve a sales tax extension by the required

supermajority in an election before 2029.

- F5. SMART’s new leadership, especially its General Manager and Chief

Financial Officer, appear qualified, energetic and motivated to take on the

many challenges that SMART is facing.

- F6. SMART does not have a comprehensive marketing and communications

strategy.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- R1. By December 1, 2023, the Board of Directors should initiate a fully

transparent, public process to be completed by April 1, 2024 that examines how

SMART might continue funding its operations beyond April 2029, including an

evaluation of when the voters would decide whether to continue levying a sales

tax for SMART’s operations.

- R2. By December 1, 2023, SMART’s Board of Directors should direct staff to

develop a written strategic marketing communications and public outreach plan

and budget focused on educating voters in Marin County about the community

benefits derived from the continued operation of the SMART rail system.

- R3. SMART’s Board of Directors should consider hiring consultants to help

evaluate the feasibility and timing of future tax measures.

On April 2029 the ¼ percent sales tax expires.

Since Marin and Sonoma county voters in 2008 authorized the sales tax

the public have invested more than $600 million.

Since trains first began operating in 2017, the weekday average ridership has

rarely exceeded 2,500. ( 1,250 ROUNDTRIPS)

Even though SMART’s ridership has rebounded after the Covid-19 pandemic,

current ridership remains short of expectations.

Without more riders the public may not be convinced of SMART’s value.

Even though SMART’s new leadership, especially its General Manager and Chief

Financial Officer, appear qualified, energetic and motivated, SMART’s Board of

Directors (Board) has yet to engage in a comprehensive marketing and outreach

strategy to increase the number of riders.

The Grand Jury has found that SMART is highly dependent on sales tax revenues

for its operations.

Without those funds SMART will not be able to continue even if it substantially

increases the number of riders or obtains additional federal, state, or regional

funds from existing programs.

In fact, SMART will likely be forced to discontinue

services if Marin and Sonoma county voters do not approve a

sales tax extension by the required

supermajority in an election before 2029.

........ cut ......

DISCUSSION

As the March 2020 election results made clear, voters did not believe SMART’s

Board and existing management had accomplished what they promised, nor did

voters have confidence and trust in the Board’s performance.

11 The Board and management team have

difficult tasks ahead of them.

They must continue to construct and improve the system and regain public support

in the organization’s mission.

In 2021, a newly hired General Manager and his new management team recognized

their principal mission was to review ongoing operations and identify and plan

for future challenges and opportunities.

To help them accomplish these goals, last year they crafted a SWOT

(Strengths, Weakness, Opportunities, and Threats) Analysis (a widely used model

or technique designed to help organizations focus their projects more clearly

and effectively).

The Grand Jury applauds the General Manager for undertaking this effort.

Since SMART is using this model to assess its own operations and future plans,

the Grand Jury believes it can be the criteria against which SMART can be

measured and also provide the general public an assessment of where SMART stands

today.

......... cut ........

They have been successful in obtaining funding. Most recently, their

continuing efforts have resulted in obtaining a substantial share of the funding

from the Regional Measure 3 toll program required to finish constructing the

route to Windsor and Healdsburg.12

Last October, SMART announced it obtained $10 million from the State of

California’s Transportation Agency and $2 million from both the city of Petaluma

and Sonoma County’s Transportation Authority to build the 13th station, North

Petaluma.13

SMART has operated its trains as planned with 30 minute headways. When the

system expanded from Larkspur north, the number of daily weekday trips increased

to 36. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic the number of scheduled trains

declined substantially. In October 2022, SMART finally reached its goal of 38

weekday daily round-trips.14

SMART reported in 2020 that “nearly 20 percent of its riders brought bicycles

onboard” and “nearly 65,000 bike/walk trips monthly across nine locations in

Marin and Sonoma counties.”15The Grand Jury calculated from the monthly

ridership reports that in 2022 approximately 15 percent of the boarders brought

along bicycles.16 Evidently, SMART’s connection with bicycle riders appears to

be working.

SMART’s Weaknesses

While a traditional “SWOT” analysis considers an organization’s “weakness” to

be reflective of an organization’s internal deficiencies, the Grand Jury has

focused on SMART’s major weakness which is low ridership. Without more riders,

public perception of the system’s value will continue to decline.

Low ridership

SMART has failed to meet its own projections or goals for ridership.

SMART’s 2006 Final Environmental Impact Report projected that by 2025 it would

carry approximately 5,050 riders per weekday.17

When the trains began operating, SMART temporarily reduced its ridership goal

to 3,000 riders each weekday. Yet, as of March 2023, SMART’s General Manager,

Eddy Cumins, promoted the goal of 5,000 riders per weekday.18

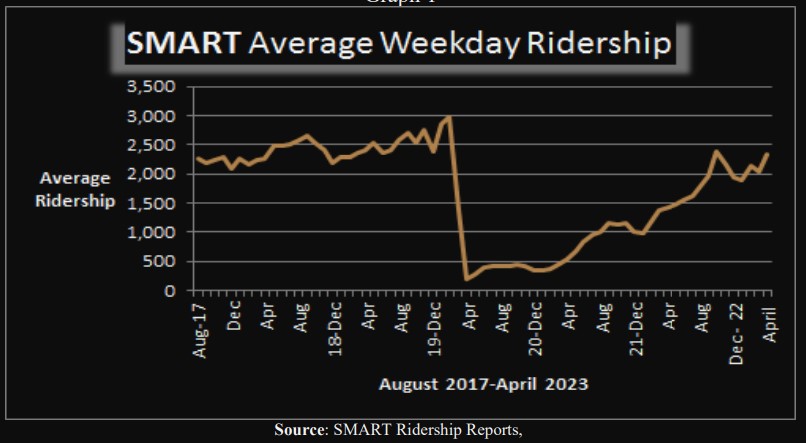

Actual ridership on the SMART system since it commenced operations has been

considerably less. Graph 1 illustrates the average number of weekday riders

since the start of operations.

The data illustrates a slight increase in the number of riders when service to

Larkspur was initiated.

Graph 1 also illustrates that prior to the impact of COVID-19 in March 2020

SMART ridership fluctuated between 2,000-3,000 riders per weekday, rarely

approaching or exceeding 3,000 riders per weekday.

In April 2023, SMART’s weekday average ridership was 2,340 passengers.19

Source: SMART Ridership Reports,

https://www.sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Ridership%20Reports/SMART%20Ridership%20Web%20Posting_Apr.23.xlsx

, Accessed on 4/28/23.

SMART’s ridership has not fully recovered to its pre-pandemic

level. On the plus side, over the past year SMART’s average weekday ridership

ranged between 68 and 97 percent of its prepandemic number. Its post-pandemic

experience is better than both BART and San Francisco’s Muni operations, which

have been less than 40 percent. 20

Nevertheless, the system continues to experience lower than

anticipated ridership. There are several factors which have contributed to this

phenomenon. In the first place, the system was limited by the use of only a

single track, minimizing the number of trains operating at one time and reducing

the probability of more riders. A second cause is an underfunded marketing

program. Most critically, however, less than anticipated riders occurs because

of what is known in transit parlance as the “first/last mile” conundrum.

The “first/last mile challenge”

A major hurdle for all public transit operators, including

SMART, is getting riders out of their automobiles and onto public transit. This

is the “first/last mile challenge.” The problem is the result of several

factors, some in SMART’s control and some not. Issues involving parking

availability, bus and ferry system transfers, the bicycle pathway, and links

with employers are all within SMART’s control. SMART is a system that, in

contrast to other Bay Area transit agencies, has fewer potential riders,

operates on a route with stops that are not close to many residences or large

employment centers, and its route is such that it does not serve as many

commuters as do other public transit agencies.

SMART’s Opportunities

“Opportunities,” in the language of a SWOT analysis, tells the

Board and management to look outside the organization for new customers.

Increasing ridership should be SMART’s number one operational goal. Increasing

the number of riders is highly correlated to an attractive fare structure,

reliability of service, improvement of first/last mile connections, and building

public confidence in the Board and management.

A marketing plan

SMART’s “shortage” of riders has been known and discussed since

the system’s inception and certainly once the trains began operating. At the

time, numerous commentators noted it would be difficult for SMART to attract

riders.21

SMART’s 2022-2023 budget proposed spending only $250,000 for

communication and marketing purposes.22

Given SMART’s ridership goals, the Grand Jury finds the lack of

a comprehensive, multi-level communication and promotion effort to attract

additional riders to be perplexing.

The “first/last mile” challenge—getting to work, home, jobs,

and the airport

SMART has considerable “opportunities” to increase its ridership

by focusing on improving its “first/last mile” connections. The 2009-2010 Marin

Civil Grand Jury recognized this need and recommended that SMART create programs

designed to encourage both employers and employees to use its trains.23

The opportunity to help Marin’s workforce was clear. In 2018,

the Transportation Authority of Marin (TAM) found that twenty eight percent of

Marin’s commuters arrived each morning from Sonoma County locales.24

Recently, SMART has made improvements in station parking, and

two months ago established a three-year, $1.1 million trial program to connect

Sonoma County Airport with the Airport Station.25

The “first/last mile” challenge—building residences, retail,

and jobs near SMART’s stations

Public transit systems have cooperated with local governments

and developers to increase housing adjacent to transit stops with the dual

objectives of increasing ridership and building more housing.26

For example, Novato is considering linking the San Marin station

to a mixed housing/retail project, the former headquarters of Fireman’s Fund

Insurance Company, less than ½ mile away.27

Conversely, Petaluma’s City Council recently turned aside a

housing plan adjacent to the new North Petaluma (Corona Road Station) that would

have provided 500 residences, parking, and revenue for both the city and SMART.28

SMART has begun making contacts with major retailers and

employers.29

The bicycle-pathway is another way SMART has chosen to deal with

the first/last mile challenge.30

Regaining the public’s trust and confidence

Another “opportunity” arises because the general public, as the

Grand Jury has heard in interviews, via direct observation, and in published

reports, lost confidence and trust in SMART’s Board and prior management team.

The failed passage of the sales tax extension in March 2020 was attributed

partially to the public’s questioning whether the Board and management were

being fully transparent.31

When SMART was created and voters were asked in 2008 to approve

a tax measure, advocates promoted the idea that it would be open to public input

and scrutiny. Voters were promised the creation of a “Citizens Oversight

Committee (COC)…to provide input and review on (SMART’s) Strategic Plan” and to

conduct an ongoing review of the System’s finances.32

The value of this independent citizens oversight body was

highlighted by both the 2013-14 Marin Grand Jury and the 2021-22 Sonoma County

Grand Jury.33

After the 2020 defeat of Measure I, the Sonoma County Grand Jury

reiterated a concern that SMART’s Board and prior management team neglected or

chose not to solicit input from the Citizens Oversight Committee.34

It found that the SMART Board’s lack of citizen input

contributed to voters’ distrust or disbelief of the system’s financial need and

thus led to the defeat of the 2020 Measure I.35

SMART’s Board just recently acknowledged the problem and agreed to accept the

Sonoma Grand Jury’s recommendations “ensuring that COC will have an opportunity

to provide timely feedback to the SMART Board of Directors.”36

The SMART Board and new General Manager have taken several

steps, including “listening tours,” designed to solicit greater public input

from those who have been critical of SMART’s decisions.They also promised to

have the COC’s reports become public and available on the SMART’s website.37

Other sources of available revenue

Even sales tax collections have been insufficient to both

operate and build the complete system.

Nearly every public transit agency in the country uses federal funds, and often

state programs as well, to build their systems.

Recently, the federal government and the State of California have expanded their

programs to also help pay ongoing maintenance and operating costs.

The federal government’s program provides SMART approximately $4 million

annually for preventive maintenance.

By 2025, SMART will be eligible to receive funds from another federal program,

called “State of Good Repair,” that is expected to provide about $6 million

annually.39

State of California public transit assistance programs have

supplied SMART with additional funds for both capital and operational purposes.

SB 1, the State Rail Assistance program, allocated more than $21 million for

SMART’s operations.40

Additional funds have been received from Metropolitan

Transportation Commission programs designed to help construct the bicycle

pathway.41

The Grand Jury has investigated possible alternative funding

sources for SMART operations, besides the sales tax, that exist or might become

available prior to 2029. One new source of funds San Francisco Bay Area voters

approved in 2018 came from increasing bridge tolls (Regional Measure 3). The

money, which is restricted to capital improvements, was not distributed until a

court challenge was finally decided in January 2023. This measure allocated a

large share of the funding necessary for completing the route to Windsor and

Healdsburg ($81 million) and finishing the bike paths ($3 million).42

A similar regional tax plan is currently being considered by the

Governor and Legislature. The Bay Area’s regional planning and transit bodies,

business community leaders, and legislators representing every county in the

region are expressing alarm that the region’s major transportation operators are

facing “a fiscal cliff.”43

One possible legislative response being deliberated is another

regional tax measure which could appear on either the November 2024 or 2026

ballot.44

The Grand Jury recognizes that while such a regional tax or a

similar plan may be developed and voter approval would be sought, its impact on

SMART is uncertain. The timing of a regional tax measure could influence how

voters might treat any Marin-Sonoma local sales tax measure. SMART’s Board of

Directors should monitor the progress of this proposed alternative financing

option.

The Grand Jury has not been able to identify any single or

combination of federal, state, and regional funding programs sufficient to

replace the projected $51 million sales tax annual operating revenue needed to

keep the trains running. Moreover, because the State of California’s anticipated

revenues are projected to decline significantly, the Governor and Legislature

are considering substantial reductions in state transportation funds.

Other than locally generated sales tax revenues, no other funds are guaranteed

to keep the trains operating.

SMART’s FUTURE

The General Manager’s SWOT analysis identifies SMART’s primary

“threat” to be the future of the sales tax. The Grand Jury agrees that it should

be the Board’s primary focus.

In addressing this question, the Grand Jury reminds SMART’s Board of Directors

that, while on four separate occasions since 1998, a majority of Marin and

Sonoma county voters supported an inter-county passenger train, the plan to pay

for it did not receive the required super-majority voter approval.

Local taxpayers have funded a monumental capital infrastructure project and

voters have directed SMART’s board as stewards of this investment to manage it

wisely.

The table is now set for a critical decision.

SMART’s management and Board of Directors need to make the case to voters in

Marin and Sonoma why they should continue to support a project that has fallen

short of its original goals and promises.

SMART should address and acknowledge its performance to date and educate voters

on why its continued operation is in the best interest of Marin and Sonoma

counties.

The analysis should include a clear explanation of its financing options and the

likelihood of future success.

SMART is at a crossroads – will it be here tomorrow?

=======================================================

| 1 The Citizens

Oversight Committee was the subject of a 2021 Sonoma County Grand Jury

Report which recommended numerous improvements in its procedures and

activities. The SMART Board has begun steps to implement those

recommendations.

https://sonoma.courts.ca.gov/system/files/smart-decision-making.pdf ,

Accessed on 4/3/23.

2 Sonoma Marin Area Rail Transit

Project, Final Environmental Impact Report, June 2006

http://scta.ca.gov/pdf/smart/final/final_eir.pdf , Accessed on 4/3/23.

3 Sonoma-Marin Transit District

2008 Expenditure Plan, July 2008, contained in Measure Q 2008. Page 13 MMM

14,

https://www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/rv/elections/past/2008/nov/measureq.pdf

, Accessed on 4/24/23.

4 Sonoma-Marin Transit District

2008 Expenditure Plan, July 2008, contained in Measure Q 2008. Page 13 MMM

14,

www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/rv/elections/past/2008/nov/measureq.pdf

, Accessed on 4/24/23.

5 The latest report, February 15,

2023, is titled “Planning for the Future–Extensions,”

https://sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Documents/02-15-2023--Item8--BOD.pdf

, Accessed on 4/24/23.

6 In 2008, Sonoma County voters

approved Measure Q by 73.7 percent vote while Marin voters voted just 62.3

percent in favor.

The combined vote was 69.6 percent favorable in contrast to two years

earlier in 2006 where 65.3 percent favored Measure R, just missing the

needed two-thirds vote.

7 2008 Marin County Voter

Information Pamphlet, Measure Q

www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/rv/elections/past/2008/nov/measureq.pdf

, Accessed on 3/31/23.

8 SMART Board of Directors,

Regular Meeting Minutes, October 19, 2019, pages 11-13,

https://sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Board/COC%20Documents/SMART%20Board%20of%20Directors

%20Packet_10.16.2019.pdf , Accessed on 5/23/23.

9 “SMART Decision Making,” Sonoma

County Civil Grand Jury, 2020-2021, page 2,

https://sonoma.courts.ca.gov/system/files/smart-decision-making.pdf ,

Accessed on April 3, 2023.

10 “SMART plans spending for

rail, path projects,” Will Houston, Marin Independent Journal, May 22, 2023,

https://www.marinij.com/2023/05/21/smart-plans-spending-surge-for-rail-path-projects/

, Accessed on 5/23/24.

11 “SMART, critics assess

aftermath of tax extension failure,” Will Houston, Marin Independent

Journal, March 4, 2020

https://www.marinij.com/2020/03/04/smart-to-regroup-after-consequential-tax-extension-fails/

, Accessed on 4/9/23.

12 Regional Measure 3 funds

totaling $84 million plus $146 million from federal programs; and $1.8

million appropriated directly through a congressional earmark. See “Marin

transit funding bolstered by state Supreme Court ruling,” Will Houston,

Marin Independent Journal, January 26, 2023,

https://www.marinij.com/2023/01/26/marin-transit-funding-bolstered-by-state-supreme-court-ruling/,

Accessed on 4/9/23. General Manager Report, SMART Board Meeting, January 4,

2023.

https://www.sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Board/COC%20Documents/Agenda%20Item%20%234%20-

%20General%20Manager%27s%20Report_5.pdf

, Accessed on 4/23/23 ; “$1.8 million in federal funding approved

for the design of the SMART rail extension to Healdsburg” SMART press

release, December 29, 2022,

https://mailchi.mp/sonomamarintrain.org/18m-in-federal-funding-for-design-of-smart-extension-to-healdsburg

Accessed on 4/9/23.

13 “SMART allots $14 M to build

second Petaluma train station,” Marin Independent Journal, Will Houston,

October 20, 2022 https://mailchi.mp/sonomamarintrain.org/18m-in-federal-funding-for-design-of-smart-extension-to-healdsburg,

Accessed on 4/9/23.

14 SMART Fiscal Year

2022-2023 Budget, pages B-3, B-4, https://www.sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Financial

Documents/FY_2023_Approved_Budget_06_15_2022.pdf Accessed on 4/7/23.

15 https://sonomamarintrain.org/node/519

February 8, 2023, MTC newsletter, Accessed on 4/3/23.

16 SMART Ridership Reports,

https://www.sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Ridership%20Reports/SMART%20Ridership%20Web%20Pos

ting_Apr.23.xlsx , Accessed on 4/28/23.

17 Sonoma Marin Area Rail Transit

Project, Final Environmental Impact Report, June 2006,

http://scta.ca.gov/pdf/smart/final/final_eir.pdf , Accessed on

4/3/23.

18 “SMART train officials did

well to avoid fiscal cliff facing some public transportation districts,”

Dick Spotswood, Marin Independent Journal, March 18, 2003,

https://www.marinij.com/2023/03/18/dick-spotswood-smart-train-officials-did-well-to-avoid-fiscal-cliff-facingsome-public-transportation-districts/

, Accessed on 4/9/23.

19

https://sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Board/COC%20Documents/Agenda%20Item%20%235_General%20Manager's%20Report_03.15.2023.pdf

, Accessed on 4/9/23.

20

https://sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Board/COC%20Documents/Agenda%20Item%20%235_General%2

0Manager's%20Report_03.15.2023.pdf , Accessed on 4/9/23.

21 “Arguments Against Measure Q,”

Measure Q, November 2008, Voter Handbook,

https://www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/rv/elections/past/2008/nov/measureq.pdf%20pdf?la=en

, Accessed on 4/4/23.

22 SMART Fiscal Year 2022-2023

Budget, B18, B-23,

https://sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Financial%20Documents/FY_2023_Approved_Budget_06_15_2022

.pdf , Accessed on 4/9/23.

23 “SMART: Steep Grade Ahead,”

Marin County Civil Grand Jury, 2009/10, Page 22,

https://www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/gj/reports-responses/2009/smart.pdf

, Accessed on 4/28/23

24

http://www.tam.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/6d-OD-Rpt.pdf ,

Accessed on 4/7/23. Tam is conducting a post-pandemic analysis of these

commuter and employment numbers.

25 SMART Board of Directors

Packet, April 19, 2023, Item 8,

https://www.sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Board/COC%20Documents/04.19.2023_Board%20of%20Dire

ctors%20Packet_0.pdf , Accessed on 4/26/23.

Last year, the airport had 614,00 travelers, a 26 percent growth since

2019.

26 https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Caltrain-stop-in-Redwood-City-is-focus-of-major-16664448.php,

Accessed on 4/4/23.

27 https://www.novato.org/home/showdocument?id=35310&t=638095538412570000,

Accessed 4/28/23.

28 “Smart allots $14M to build

second Petaluma train station,” Will Houston, Marin Independent Journal,

October 21, 2022,

https://www.marinij.com/2022/10/20/smart-allots-14m-to-build-second-petaluma-train-station/

, Accessed on 4/3/23. see also SMART’s Final Environmental Impact Report,

June 2006, projected a range of 400- 1,000 additional daily riders if

transit oriented housing projects are built.

Sonoma Marin Area Rail Transit Project, Final Environmental Impact Report,

June 2006,

http://scta.ca.gov/pdf/smart/final/final_eir.pdf , Accessed on 4/3/23.

29

https://www.northbaybusinessjournal.com/article/article/smart-ridership-rebuilding-but-gm-says-increasedcosts-will-temper-new-pro/

, Accessed on 4/7/23.

30 “SMART Pathway funds

programmed for Marin and Sonoma by the Metropolitan Transportation

Commission,”,

https://sonomamarintrain.org/node/519 , Accessed on 4/9/23

31 “New SMART general manager

must change the culture,” Mike Arnold, Marin Independent Journal, December

1, 2021,

https://www.marinij.com/2021/12/31/marin-voice-new-smart-general-manager-must-change-the-culture/

, Accessed on 4/7/23.

32 2008 Marin County Voter

Information Pamphlet, Measure Q

https://www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/rv/elections/past/2008/nov/measureq.pdf

, Accessed on 3/31/23.

33 Report: https://www.marincounty.org/depts/gj/reports-and-responses/reports-responses/2013-14/smart-down-thetrack

and Response:

https://www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/gj/reports-responses/2013/responses/smart_bos.pdf

, Accessed on 4/23/23.

34

https://sonoma.courts.ca.gov/system/files/smart-decision-making.pdf ,

Accessed on 4/23/23.

35 “SMART Decision Making,

Citizen Feedback is Critical For Success,” Sonoma County Civil Grand Jury,

2021- 2022, page 2.

https://sonoma.courts.ca.gov/system/files/smart-decision-making.pdf ,

Accessed on 4/7/23.

36

https://sonoma.courts.ca.gov/system/files/grand-jury/smart-decisionmaking-smartsbod.pdf

Accessed on 4/7/23.

37

https://sonoma.courts.ca.gov/system/files/grand-jury/smart-decisionmaking-smartsbod.pdf

, Accessed on 4/7/23.

38 The pandemic has demonstrated

that transit agencies highly dependent on riders are facing severe financial

challenges, a phenomenon described as

“facing a fiscal cliff.” see: “BART faces its ‘most challenging revenue

outlook’ in history as low ridership numbers persist,” Ricardo Cano, San

Francisco Chronicle, February 10, 2022,

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/BART-faces-its-most-challenging-revenue-16849200.php

, Accessed on 4/9/23.

39 “Short Range Transit Plan (SRTP)

Update – Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC)” report to the SMART

Board, January 4, 2023,

www.sonomamarintrain.org/sites/default/files/Board/COC%20Documents/Agenda%20Item%20%239%20-

%20SRTP%20Bay%20Area%20Transit%20Recovery%20Scenario%20Planning.pdf ,

page 8, Accessed on 4/23/23.

40 SB 1- State Rail Assistance

Program, October 2022,

calsta.ca.gov/-/media/calsta-media/documents/sra-approved-applications-update---20221018_a11y.pdf

, Accessed on 4/9/23.

41 “SMART pathway funds

programmed for Marin and Sonoma by the Metropolitan Transportation

Commission” SMART press release February 8, 2023,

https://sonomamarintrain.org/node/519 , Accessed on 4/24/23.

42 “Marin transit funding

bolstered by state Supreme Court ruling,” Marin Independent Journal, Will

Houston, January 26, 2023,

www.marinij.com/2023/01/26/marin-transit-funding-bolstered-by-state-supreme-court-ruling/

,

43 “Could the Bay Area Lose

BART?”, Richard Cano, San Francisco Chronicle, March 13, 2023,

https://www.sfchronicle.com/projects/2023/bart-finance-qa/

Accessed on 4/3/23.

45 “Bay Area lawmakers urge state

for more transit funding to avoid ‘irreversible’ service harm,” Richard

Cano, San Francisco Chronicle, January 19, 2023,

https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Bay-Area-lawmakers-urgestate-for-more-transit-17728841.php

and

https://mtc.ca.gov/news/broad-coalition-urges-state-craft-budget-transit-operations-mind

, Accessed on 4/3/23. |

=============================================================

SOURCE

https://www.marincounty.org/-/media/files/departments/gj/reports-responses/2022-23/smart-at-a-crossroads.pdf?la=en

|