|

The Best Laid Plans -- Planning and Affordable Housing in Marin

The End of Federal Housing

Programs

Call 'em NIMBYs

Ownership Will Save Us?

Bubble-nomics

Affordable Housing Today

What is Our Affordable

Housing Problem?

What Kinds of

Housing Do We Really Need in Marin?

The Law of Unintended

Consequences

It’s The Law?

A Cycle of Failure

Making Better Decisions

Looking Ahead

What Is the Problem

We’re Trying to Solve?

Housing Elements and Land

Entitlement

Affordable Housing Demand

Social Engineering at Its Worst

Workforce Housing

Nuts and Bolts and Finance

Affordable Housing and Social

Equity

Public Transportation and Growth

Local Voices Equal Better

Solutions

Leadership and New Directions

Working Collaboratively

APPENDICES

The Truth about

SB375 and the One Bay Area Plan

A

Criteria-Based Approach to Housing Policy for Mill Valley

Why “One Bay Area’s” Growth Plan is Not the Solution for Marin – Part I

Why “One Bay Area’s” Growth Plan is Not the Solution for Marin – Part II

An Alternative Analysis to the Development of Miller Avenue in Mill Valley

The Best Laid Plans - Part I: A Brief History of

Planning

|

“Adriana, if you stay here though, and this becomes your

present then pretty soon you'll start imagining another time was really

your... you know, was really the golden time.” ~ Midnight in Paris

– Woody Allen

In the late 1800’s, the social and economic disruptions caused by the

Industrial Revolution sparked a back-to-nature movement (inspired by the

writers like Thoreau) and utopian communities sprang up across the country.

But others believed that industrialization would bring about another kind of

utopia: one filled with scientific wonders and new opportunity for all. But

the dawning of the 20th Century brought surprises no one imagined.

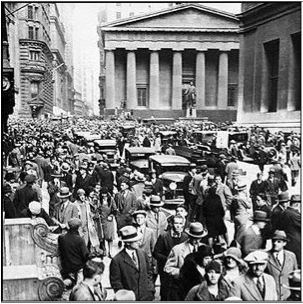

The promise of the Industrial Revolution gave way to the financial panic of

1905 (when the federal government had to be bailed out by JP Morgan), the

war to end all wars (WWI), the Depression of 1921, the Roaring Twenties and

finally the Crash of 1929. The ensuing Great Depression left the public

shaken.

By 1933, life seemed like an unending litany of booms and busts and

scandals. Distrust of big business and government was at an all-time high.

The majority of wealth was controlled by a small percentage of the

population and the disparity between rich and poor had reached

historic proportions. And the political landscape had become increasingly

polarized on the left and the right.

Meanwhile, the general public was suffering from the worst real estate

crash in history and they just wanted someone to get people back to work.

Until the crash, people had been living high on the hog but now that seemed

gone forever. People were very angry and they wanted “change.”

Sound familiar? History seems to be repeating itself, for better and for

worse. But notwithstanding the years dedicated to fighting World War II, or

ironically because of it, in the decades that followed taxes got raised,

markets and finances were regulated, the middle class thrived, and the

American century came into its own. |

Pruitt Igoe Project Demolition – St. Louis, MO 1973 – HUD Archives |

A Very Brief History of City Planning

City planning has been with us forever. Alexandria, Athens, Rome, Tikal,

Paris and Washington, D.C., were all carefully planned, albeit from the very

top down. It’s even claimed that the reason Nero fiddled while Rome burned

was because he wanted to do major urban renewal and starting from scratch

was the best way to eliminate “community opposition.” But the planning of

our towns and cities (rather than seats of government) got a major boost

from the challenges of the early 20th century when a new idea was born.

From Bauhaus to Your House in Marin

There’s something about human nature that gravitates toward big,

simplistic solutions when faced with complex problems. And faced with the

multitude of woes in the

1930’s, many believed that massive housing projects were the way to solve

our social and economic problems.

This view was shared by many social reformers and prominent architects and

planners of the time, who proceeded to take a plausible idea and completely

overdo it. “Modern” architecture and planning, as it came to be known,

embraced mass production and technological innovation and promised to create

cities that showcased the wonders of the Industrial Age. This egalitarian

and utilitarian ideal, proselytized by Walter Gropius and the German

Bauhaus, was perhaps most famously expressed by an obscure painter

turned architect named Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (who changed his name to Le

Corbusier - perhaps being the first artist to take on a one name moniker).

The Radiant City

| For “Modernists” like Corbusier, housing people was an

industrial undertaking and humanity’s needs were utilitarian (fresh air,

sunlight, sanitation, human scaled space, clean water and a view). This

culminated in a vision he called La Ville Radieuse (The Radiant

City). The Radiant City envisioned thousands of boxy, well lit,

unadorned living units stacked in towering glass, concrete and steel

skyscrapers built in close proximity to transportation (automotive super

highways) and within walking distance to shopping and other necessities

(“The more things change…”).

Unfortunately, grand visions tend to be doomed to grand failures.

To be fair, the modernists were as much driven by concern about public

health conditions for the 99 percent as they were by trying to house the

masses: there was little fresh air or natural light and few private

bathrooms in 19th century tenements and housing conditions for the

masses in general were abysmal. The times called for bold action and

optimism about grandiose solutions. Our innate love of all things new

and shiny proved irresistible.

So when our federal government looked for ways to solve the demand for

new housing in the 1940’s after WWII, they looked to Modernists'

visions. |

|

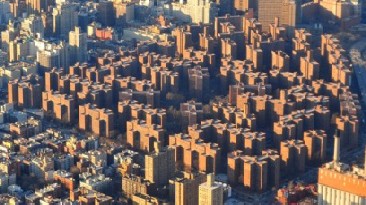

Projects like Stuyvesant Town / Peter Cooper Village

in New York City, built in 1947,

housed almost 100,000 people in one high density location (the Radiant

City in Manhattan). And the demand for housing at that time, after

decades of almost no housing construction, was very real.

Proponents claimed it had everything required to ensure its success.

It was a “walkable,” modern village close to schools, shopping and

public transportation. But what began in the late 40’s as a vision of

equality and affordable housing opportunity became a dystopian

nightmare, unflatteringly known as the "projects” by the 1960’s.

To have grown up in the projects was synonymous with having had a

deprived, crime-filled childhood that you dreamed of escaping. Somehow

“warehousing” people near public transportation and in walking

distance from shopping just didn’t magically bring about equality,

harmony or happiness.

Perhaps I’m just spit-balling here, but maybe it had something to do

with the complete lack of opportunity for individual expression and

other less tangible human

needs.

By the early 1970’s, these massive experiments in social engineering

had clearly failed and we began tearing down high density affordable

housing projects across the country. Pruitt Igoe in St. Louis (2,870

units; photo at top) was the most infamous but by no means the only

example. Yet somehow this lesson continues to escape the “one size

fits all” central planners today. |

|

By the 1980’s and early 1990’s, it became obvious

that we needed a new take on things. Fiscal conservatism became

the new fashion and federal funds for housing were drying up

faster than the Sacramento River Delta. Consequently, city

planning became more about urban renewal, historic preservation

and zoning codes than about building cities of the future. Left in

a lurch, planners swung 180 degrees in the other direction and

embraced the back-to-nature utopian ideals of the last century,

but this time with a new twist. This was a new kind of nostalgia

for the past that came wrapped in a new phrase:

“sustainable living.” It was called “New Urbanism.”

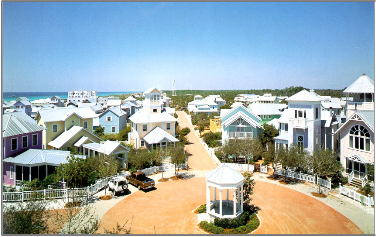

Towns would now instantly have all the “character” of small town

Americana. New

Urbanism preached the benefits of walkable communities

near shopping, amenities and public transportation. It was based

on observing successful small towns (like our towns in Marin)

and attempted to reproduce the lifestyle they enjoyed. The only

problem is there’s a lot more to what creates “community” than

meets the eye. |

|

New Urbanism envisioned winding streets lined with

quaint Craftsman-like clapboard homes on small lots, with people

chatting with neighbors from rocking chairs on wooden porches

behind white picket fences. Neighborhoods were laid out around

quaint “town squares” with housing districts separated from

commercial areas by green space. In many ways these plans were

almost an exact copy of the utopian towns that were designed and

built in the U.S. from the late 1800’s and the early 20th

century.

There’s no argument that there are compelling reasons for living

in a more humanized environment. Just ask anyone who lives in

Marin. But at the end of the day, the New Urbanism vision is

superficial and its “community” is as faux as the shiplap siding

on its cutesy bungalows.

New Urbanism is like Ralph Lauren was in the 1980’s. Both

try to sell us a nostalgic, patina-tinged vision of a past that

never actually existed. Rather than doing the hard work of

rethinking our world from the bottom up, addressing

inter-related socio- economic realities and offering a truly new

vision of our future potential, New Urbanism offers us a

sentimental throwback to a Norman Rockwell painting belief about

who we are. But in the face of our 21st Century challenges, it’s

devoid of sustainable answers because we are not those imaginary

people and we don’t live those imaginary lives. New Urbanism

planners have made their careers out of selling a vision of

simpler times to a world-weary public. But in reality, the

promises of New Urbanism are empty. |

|

Interestingly, New Urbanism was originally conceived to

improve upon and make some sense out of suburban sprawl. It is

actually mislabeled. It should be called “suburban-renewal.” It

primarily focused on better ways to build single family housing in

places completely devoid of character (Laguna West near

Sacramento, Denver Stapleton Airport Redevelopment, etc.) and

hoped that suburban commuters would someday be served by better

transportation options like light rail.

These were perfectly legitimate goals. But New Urbanism

wanted to get people out of cars mostly to enhance social

interaction and small town character, not because of presumptuous

claims about mitigating climate change. Likewise, New Urbanism

was not originally about affordable housing. But in an attempt to

remain relevant, it has been turned to the

dark side.

Planners like Peter Calthorpe now work for major suburban

developers like Forest City Enterprises, and New Urbanism

has become synonymous with social engineering by big government

agencies promoting infill, high density housing near freeways.

This unfortunate fusion has given us what might be described as

the worst of both dystopian worlds: the faux “sustainable”

community of the “back to simpler times” movement combined with

the high density near transportation / housing for the masses

visions of the Modernists. And in the middle, real communities

like ours in Marin, which were built on decades of local control

and environmental protection, are being thrown under the bus in

the name of progress.

The result is projects like the 180-unit WinCup development,

located next to the 101 highway off ramps in Corte Madera,

and the Millworks mixed use project in Novato (Whole Foods

and condos). Building projects like this as “infill” won’t make

them work any better than their larger scaled predecessors. It’s a

sure bet that in 20 years these will not be among the most

desirable places to live in Marin.

Perhaps the most absurd irony of all though is that we now have

Peter Calthorpe coming to Marin to preach to us about the virtues

of New Urbanism when in fact it is towns like ours that were the

inspiration for New Urbanism in the first place.

I think our citizens know better than anyone what “community” and

“walkable neighborhoods” and “small town character” are. The

New Urbanism planners of the world should be coming to

Marin to learn not to preach. We don’t need their definition

of “sustainable” but they sure do need ours. Yet we find ourselves

having to fight against the New Urbanist

mantra to preserve what we have: the very thing they

profess to want to create. Figure that one out.

In truth, New Urbanism’s solutions are not really more

sustainable. Their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions savings are

nonexistent (Appendix A).

Their building methods are conventional and just as

environmentally destructive as anything else. And implementing its

concepts without first addressing the underlying social and

economic causes of social inequity is fiscally irresponsible.

Who’s not for

a Sustainable Future?

Let’s face it. Everyone is for “sustainable solutions.” But

those solutions need to actually be socially, economically and

environmentally sustainable after considering their true costs of

“natural capital” and their external affects (supply chain energy

usage, third world environmental degradation, etc.; also see

Natural Capitalism by Paul Hawken). New Urbanism and

the One Bay Area Plan approach are not that. What we really

need are solutions that are truly environmentally sustainable

and address our social equity challenges at the same time. We

need solutions that make fiscal sense for our cities and financial

sense to private capital markets.

That is the problem before us. But instead we find ourselves faced

with an unappetizing menu of “high density” options and massive

bureaucracies trying to force one size fits all solutions down our

throats (Appendix

C), none of which are really sustainable in any real sense of

the word.

But there was a third vision that came out of the 1930’s that was

totally ignored in its day and has been derided by historians ever

since. Its author was not a popular man. He was the quintessential

“politically incorrect” designer of his time. But it was the only

vision that actually addressed long term sustainability. Maybe

there are things we can learn from it.

Photo Credits The Radiant City – Wikipedia

Foundation Stuyvesant Town / Peter Cooper Village – Wikipedia

Foundation Seaside, Florida – Seaside Marketing Brochure

Stapleton Redevelopment – Forest City Development

The Best Laid

Plans - Part II: 21st Century Planning

|

“The Internet is based on a layered, end to end

model that allows people at each level of the network to

innovate free of any central control. By placing intelligence

at the edges rather than control in the middle of the network,

the Internet has created a platform for innovation.”

~ Vint Cerf

When you develop Internet software, the only thing you can

be sure of is that everything you’re sure of will probably

change because innovation is happening everywhere in the long

tail. It is the ultimate “bottom up” system. This means that

designing for it requires solutions that embrace user

interactivity, open-ended design, flexibility, and methods

that “learn” and adapt to change. I think city planning can be

that way. In fact I think it will have to be because whether

we like it or not, the coming century will be an increasingly

bottom up, networked, borderless, telecommuting, personally

expressive, crowd-sourced world.

I know. It sounds like a lot of big words. But think about it.

I recently wrote a piece about a “criteria-based method” of

planning (Appendix

B). It suggests an approach that would be more responsive

and adaptable to the nuances of local public policy needs and

the ever-changing dynamics of private capital markets. It

highlights the importance of enabling individual initiative

and local empowerment in solving planning problems. And in

some ways it was inspired by the third planning vision that

came out of the 1930’s. |

Broadacre City, 1935 – Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation |

The Bad Boy of

Planning

Frank Lloyd Wright was perhaps the most controversial

architect in modern history. His iconoclastic career was unique

even among American visionaries. Always the rebel, he never

bothered to get a license to practice until he was in his 70's,

by which time he'd designed or built more than 600 buildings. By

today’s standards he’d be called a Libertarian (footnote: The

Marin County Civic Center was Wright's last commission before

his death).

Wright absolutely hated top down planning and big government.

He’d be rolling over in his grave if he knew about ABAG

(Association of Bay Area Governments) and One Bay Area Plan.

When it came to city planning, Wright was a staunch advocate of

“local control.”

Wright called his planning vision Broadacre

City. Like the other planning concepts of the Depression

Era, its goals were to enhance the fortunes of the common

man by creating a more egalitarian society. But after that

it diverged completely from the orthodoxy of Modern urbanism

because it wasn’t urban at all.

Universally dismissed by critics of the time, it turned out

to be the most durable idea of all because it foresaw the

rise of suburbia. In fact it has been blamed for all the

ills of suburbia but that’s just because Broadacre City’s

concept was never fully understood or appreciated.

Unlike the Modernist’s high-density, glass and concrete

cities or utopianism’s back to nature schemes, Broadacre

City might be called the "40 acres and a mule" school of

planning. Wright aimed for a balance between nature and

man’s footprint on the planet. He was a strong proponent of

individual creativity and personal self-sufficiency long

before it was fashionably called “sustainable.”

Wright envisioned an adaptive plan wherein every family had

its own sustainable one acre plot, large enough to grow some

food, capture rainwater, have a windmill and raise a few

animals. He envisioned "growth" as an organic process that

was mostly horizontal, with occasional instances of high

rise development (his famous “mile-high” skyscraper design

being an example of that). |

|

Now there’s no doubt that Wright’s ideas were in some

ways even more fanciful than the other planning visions of

his time. But Wright was essentially talking about living

"off the grid" or at least not being dominated by it. Like

the way the Internet is managed today, he was talking about

planning that had no central control point but was designed

and developed by local

users for local

conditions “at the edges,” all within a flexible framework

that optimized outcomes for all. In this respect, he was way

ahead of his time.

Technology

and Sustainability

SB 375 and the One Bay Area Plan approach tell us

that we have to accept the Modernist / New Urbanism high

density near public transportation vision of the future. The

argument is based on claims about mitigating environmental

impacts. It's a rigid and single-minded view of the future

in which suburban living is singled out as a major problem.

But it's not based on facts.

As I've shown before, their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions

savings assumptions are seriously flawed (Appendix

A), and they incorrectly assume that the things we make

(our vehicles, buildings, appliances, etc.) are immutable

givens that will never change.

This is the basis for their GHG calculations and rationale.

But there’s no evidence that this is true or even likely in

the future.

Vertical, high-density cities are not, in and of themselves,

a sustainable solution. They are an "economic" solution and

perhaps a "social" solution. But today, cities like New York

City are, on a per capita basis, the most egregious

polluters on the planet, not just in terms of GHG emissions

but also when one accounts for all the impacts on

surrounding regions to “feed” them with water and power and

deal with their waste. And regarding

SB375’s assumptions about polluting automobiles, vehicle

technology not only can change but it is

changing dramatically as we speak (the 2013 Ford C-Max

Energi is a plug-in hybrid that will get more than 110 mpg).

All this considered, shouldn’t we be planning for the future

instead of the past?

New technology offers us other options. The ability to

produce zero pollution and super energy-efficient vehicles,

buildings and mechanical equipment is within our reach. It

only requires national, state and local public policy to

make it happen (just as agri-business and oil and gas

subsidies make those things happen). But there is another

"elephant in the room" that is not even acknowledged by the

One Bay Area approach, though it may be even more

important than all the rest.

Power,

Water and Waste Systems

Achieving a sustainable future and “planning for change”

also includes how we distribute power and water and collect

and process waste. Throughout history the need to share and

efficiently distribute resources from a central location

(e.g. water from a river or natural spring) has been a

given. This is so ingrained in our thinking that we accept

it without questioning its long term sustainability

challenges. But by all measures centralized utility systems

are incredibly wasteful and inefficient. This gets even

worse in suburbia where the distances between users and the

sources of power or water or the distance to sewage

treatment plants is greater.

Significant losses occur as electrical power moves out

through our vast centralized power grids. A large percentage

of our drinking water is lost due to leakage and evaporation

as it moves through underground pipes and aqueducts. And in

many U.S. metropolitan areas, 50 percent of the effluent

that goes into sewer lines never reaches the treatment plant

because it leaches out into the ground through old pipes.

And then there’s the cost of building and maintaining these

centralized systems and the support services, which create

even more pollution and waste.

When it comes to really addressing our environmental

challenges and the host of options at hand, all this becomes

very important to consider because efficient use of

resources is fundamental to any environmentally or

economically sustainable solution. So we have to ask

ourselves, is there a better way? And if there is, what

model should we be looking to for guidance?

The Nature of Nature

The history of the world is the history of going from

simplicity to diversity, from single-celled organisms to

multi-celled marvels, and from isolated linear systems

to complex inter-related networks and “systems of

systems.” Throughout that process, nature’s

problem-solving methods have favored bottom up and

locally driven solutions that allow for the nuances and

constraints of local conditions.

But there are more benefits to nature’s way than

respecting local control and encouraging diversity.

Nature’s top-to-bottom and bottom-to-top interactive

feedback methods tend to result in solutions that are

the most energy, time and resource efficient possible

for all participants. Because of real-time interactivity

between local and global, nature’s methods are

constantly optimizing outcomes for all.

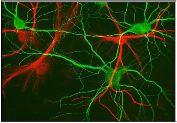

Consider three examples: the way your brain is wired,

how a vine grows on a fence and the infrastructure of

the Internet.

Each is elegantly adapted to solve “local” problems

in a way that addresses specific needs, and at the same

time allow the entire networked “organism” to operate as

efficiently as possible without central control. This is

the secret of their success. |

|

21st Century Interactive Planning

City planning has followed the same trajectory as

nature, evolving from enclosed city states into networks

of cities separated by vast expanses, until the edges of

cities expanded to the point where everything got

connected and we have the megalopolis we live in today:

networks of inter-related entities with both shared

concerns and unique problems. But we’re at a tipping point

in history. The top-down, centrally controlled state and

regional planning methods that made sense in the past are

now too rigid and unresponsive to address the complexity

of our contemporary world.

Looking ahead, what we need are methods that enhance

greater interaction between the top and the bottom,

maximize local input and local control of planning

decisions, and encourage diverse and novel solutions. The

implications of this for our political process, legal

framework and planning hierarchies are enormous.

Interactivity even suggests the need for our

representative form of government to finally transform

into a "one person, one vote" true democracy.

This brings us back to Frank Lloyd Wright. It's important

to recognize that the fundamental limitations of Wright’s

sustainable concepts were technological. The technology

required to make his ideas feasible simply didn’t exist.

However, today we have the ability to realize Wright’s

self-sufficiency and environmental / community /

sustainability goals.

In the near future every vehicle we produce will be

pollution free and run on sustainable power (electricity,

hydrogen, biofuels, etc.), and every building could be

carbon neutral and produce most of its own power. And

buildings could harvest and recycle grey water and treat

much of their waste on site (see photos).

Consider the following:

Water: Water conserving appliances and

equipment, drip irrigation, rainwater capture and gray

water recycling can dramatically reduce the amount of

water needed and force us to rethink our water

distribution methods (this is already

happening enough to

put the Marin Municipal Water District’s business model in

jeopardy).

Waste: “Closed-loop” waste technology

that separates and treats waste on site has been around

for more than 40 years. It's time that this was given more

careful consideration. These systems can greatly reduce

the need to expand or upgrade sewer systems and can

increase the opportunities to produce recycled waste

products. Recycling and banning plastic bags is just the

tip of the iceberg of the change that is possible when it

comes to dealing with our trash.

Energy: Advances in energy-conserving

products and alternative energy sources are about to tip

the balance of global energy production and distribution

from the top to the bottom. Feeding power in one direction

out to users on the grid, from central power plants (i.e.

hydroelectric plants, nuclear reactors, coal fired

generators, etc.) is technologically obsolete. “Smart

Grids” distribute power the

way the Internet distributes information and

dramatically alter the “user / producer” relationship.

They change a “distribution” network into a “sharing”

network where everyone becomes both a user and a producer.

New thin-film photovoltaics can produce solar energy on

any surface (even window glass). Wind is the fastest

growing new energy source in the world and residential,

rooftop wind generators should start showing up at Home

Depot within the next decade. More options will be here

sooner than people think especially if we encourage them.

As Amory Lovins

has so famously said, it’s all about “reduce, reuse,

recycle.” Every product we manufacture needs to address

its energy consumption and waste output and be

100 percent recyclable. This is true for the buildings

we build, the vehicles we drive, the food we grow, and the

gadgets we consume with abandon (it's called "Cradle to

Cradle" design). Even things like urban farming are

transforming our cities and demonstrating the efficiencies

of solving "demand" problems at the source.

But again, this won’t happen without public will and

public policy to support it. So if our government is going

to provide financial incentives for anything, perhaps this

is money better spent than the hundreds of billions we

spend annually subsidizing military arms, oil and coal,

and sugar and corn.

What Does This Have To Do With Planning?

All this suggests that future growth may be much more

about renovation, reuse, conservation and technologically

retrofitting what we already have (like putting rooftop

solar on every building) than about “scrape and build”

construction and the grandiose planning methods that

dominated the 20th century. This is not science fiction.

These are the things we have to do if we ever hope to

offer the next generation a reasonable future. And if even

half of what I’m suggesting comes to pass, it will have

profound implications for the future of planning.

If adaptive technology can re-engineer our lives and

automobiles will no longer pollute or rely on fossil

fuels, then all the "urban" versus "suburban" arguments

fall apart. In fact lower density suburban solutions may

have significant environmental and quality of life

advantages over high density urban solutions. At the very

least, there’s room for a wide variety of locally driven

solutions, all of which might be equally sustainable and

all of which should be on the table for consideration

instead of the one-sided thinking we’re being force-fed by state and regional agencies (ABAG/MTC/BCDC/BAAQMD).

Solving

Problems at the Source

I live in a 1,830-square-foot house on a 50 by 125 ft.

lot. I have landscaped yards with six kinds of fruit trees

and a sizeable vegetable garden, all fed by automated drip

irrigation. I compost most organic waste and produce very

little trash. I drive a hybrid car. My appliances and

fixtures are energy saving and low flow. My electric bill

averages less than $90 per month. For almost that same

monthly cost, on a leased basis, I’m considering

installing solar panels which

would provide 100 percent of my electrical needs now and

when I purchase a plug-in electric

car in the future. If I had a

rainwater capture and grey

water waste recycling system, I’d pretty much be

off the grid, or in the case

of electricity, selling back to the grid.

Someone please explain to me how this is not a

sustainable solution.

Someone please explain to me why we’re not creating every

incentive we can to allow everyone to

renovate and retrofit their homes to

live this way, or why all new residential

(single family and multifamily) and commercial buildings

shouldn’t be designed to have far less environmental

impact (LEED – Leadership in Energy and Environmental

Design - is not enough). Public policy supporting this

would create thousands of new businesses and tens of

millions of 21st century hi-tech jobs across the country

(versus short term, low pay construction and service

jobs).

Why is it we're not hearing anything about these options

from ABAG / MTC and our elected officials? Have we

really become that unimaginative or that pessimistic about

our future? How can we expect anything to change if we

don’t bring about change right here in our own

communities? Do we really want to bet our future on the

dismal, over-reaching plans of engorged government

agencies?

The arguments that "urban" is good and "suburban" is

bad, or "high density" is superior to "low density" are

off base. Our path to a better future is through solving

problems in the most efficient and mutually beneficial way

possible. And I believe that it's the right combination of

financial backstop from the top and locally driven public

policy and decision making at the bottom that can best

ensure that outcome.

Looking Ahead

Myopic high-density scenarios like the One Bay Area

Plan are out of synch with the multi-faceted way the

future of our cities and infrastructure is likely to

unfold. It deals in fixed absolutes and views things from

only one direction: producers to users, sellers to buyers.

Jobs and workers are just numbers devoid of human

proclivities and choice. It fails to account for our

increasingly interactive world and how creative, private

capital and public policy changes can dramatically effect

predictions based on the status quo.

This is particularly critical right now because don't have

the luxury of unlimited resources or unlimited wealth to

squander on bad ideas. The faulty assumptions of laws like

SB375

(Appendix A) will lead to more bad decisions and more

misallocation of taxpayer money. And applying its faulty

logic to other challenges, like affordable housing,

has already led to even more damaging proposals like

SB1220 (more local taxes and fewer local benefits)

and SB226

(eliminating CEQA review for "infill" projects),

which undermines the very thing SB375 pretends to

be trying to preserve, our environment.

It’s a road we cannot afford to go down.

Over-reaching top-down social engineering has failed us in

the past and it will fail us again. Its approach is

economically destabilizing and financially irresponsible

because it contradicts the laws of supply and demand, free

markets, and the way communities naturally grow and

thrive. And it’s ultimately environmentally destructive.

And for what?

But if all that’s true, then how do we address our

legitimate social justice and affordable housing concerns?

And what about the portion of our population that is truly

in great need, the people we really should be focusing on

who are just getting by and need a helping hand or a

“safety net” right now?

Photo Credits Broadacre City – Frank Lloyd

Wright Brain Synapse – Scientific American Vine on Fence –

Public Domain Internet Layout – Public Domain

The Best

Laid Plans - Part III: Affordable Housing

|

“Those who cannot remember the past are

condemned to repeat it.” ~ George

Santayana

When I was growing up in New York City, where my

family owned a small business, my father told me that

the scariest words in the English language were,

“We're from the government and we're here to help

you." A lot of people feel that way about ABAG

housing quotas and

affordable housing projects

in general. But it’s more complicated than that.

Reasonable people might agree that having a variety of

housing opportunities for those most in need, without

discrimination, is a worthy societal goal. But there’s

a difference between “providing housing opportunities”

and “building affordable housing.” And affordable

housing means different things to different people in

different places. It includes homeless shelters,

starter homes, rental apartments and townhouses,

live/work lofts, SRO (single room occupancy) housing,

elderly housing and assisted living, housing for very

low and low income (below 30 percent to 50 percent

median) and 80 percent median income “affordable”

units like the ones we see being built all over Marin

(for a family in Mill Valley earning about

$90,000 per year).

So where should we focus our efforts and how do we

define and prioritize our needs? Some history of how

we got here helps. |

Dexter Asylum (Poor House), Providence RI 1824

- Library of Congress |

A Brief History of Affordable Housing

Affordable housing in the U.S. was traditionally left

to private markets or corporations that built “company

towns” for their workers (e.g. Pullman, Illinois (see

photo) and Scotia, California). But the idea that the

government should get directly involved (other than

operating “poor houses” for the destitute; see photo)

didn’t really come into being until the Great

Depression.

In 1934, the National Housing Act created the

Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to help people

protect their homes from foreclosure. The 1937

Housing Act, which coined the phrase “affordable

housing,” subsidized the construction of

government-owned rental housing for the general public

under Section 8 of the Act. After that the

federal government quickly became the primary driver of

affordable housing construction and finance.

The mid 1940’s through the early 1960’s was the Golden

Age of government housing. The 1949 Housing Act

and urban renewal legislation caused a building boom

across the country to feed post World War II demand.

Projects like Stuyvesant Town / Peter Cooper Village in

New York City, built by a “public–private partnership”

in 1947, housed almost 100,000 people in one location

(see Part I).

The Winds of Change

The 1960’s saw the passage of Fair Housing laws to

ensure equal access to housing, an important

advancement. But in the aftermath of the Vietnam War the

nation turned more conservative. The costs of the war

and Johnson’s Great Society had been enormous. One of

Richard Nixon’s first actions as president in 1970 was

to cut federal housing programs dramatically. The

thinking was that we were sinking too deeply into debt

and could no longer afford them.

To replace some of the financial shortfall, the

Community Development Block Grants program was

created in 1974 and modifications were made to

Section 8 housing programs to allow low income

renters to live in privately owned buildings. Signed by

Gerald Ford, these changes eliminated a good number of

government-built public housing programs so construction

started shifting back to the private sector. These were

the first substantive changes since the 1930’s. But the

real turning point came when Ronald Reagan was elected

in 1980. This marked the beginning of the end of HUD’s

central role in providing affordable housing and the

beginning of the “markets can solve everything”

mantra.

The End of Federal Housing Programs

One of Reagan’s stated goals was to get the federal

government out of the housing business completely, and

so the systematic dismantling of affordable housing

support systems began in earnest. In 1983, a

Reagan-appointed commission recommended an end to all

project-based Section 8 subsidies, except in the case of

rehabilitation. They recommended that all subsidies

shift to housing vouchers to give private

developers incentive to build affordable housing

(vouchers are a rental payment coupon that a renter can

use to live anywhere). No new government-owned housing

projects were approved for construction after Reagan’s

election.

Jack Kemp, a self-described “bleeding heart

conservative” and arguably one of the most important

architects of HUD’s recent history, became

Secretary of HUD in 1989. Prior to that, he worked

behind the scenes to help the Reagan Administration

“privatize” the affordable housing business.

Co-insurance, wherein private banks took over the role

of financing projects in exchange for government

guarantees of their debt, became widely used. Housing

“project revenue bonds” and leverage debt became

fashionable methods to finance private development

without personal risk. And newly created Low Income

Tax Credits attracted investment banking, mutual

fund and corporate money to fund projects that had

federal Housing Assistance Payments (HAP) Contracts

in place to guarantee high rents.

This all worked great for a while until unscrupulous

underwriting practices and too much leveraged debt

brought on the Savings & Loan Crisis in the

1980’s (which we have to thank for coining the phrase

“too big to fail”). When it was over,

multifamily development was

stalled for years and the banking fiasco became

another excuse to get rid of

government housing programs altogether.

The Knock-Out Punch

In the final coup d’état, the Office of

Independent Council launched a massive investigation

into “political influence peddling” at HUD in

1988. The investigation was based on the “shocking”

revelation that subsidy grant decisions in Washington

might be influenced by political favoritism and high

paid lobbyists (OMG, there’s “gambling at Rick’s”). This

seems quaint today and it had little to do with routing

out corruption, but secretaries went to jail while high

rollers walked away scot free. And federal affordable

housing programs never recovered.

Project-based subsidies (projects with HAP contracts)

were greatly reduced. Co- insurance and renovation

programs like the Moderate Rehabilitation program were

scuttled. And all that was left were Section 8

vouchers and tentative annual allocations of Low

Income Tax Credits that almost exclusively went to

big nonprofit developers who resold them to major

corporations and investment funds. But as bad as all

this was, it was only the beginning.

Call 'em NIMBYs

In 1991, HUD issued a report entitled, “Not

in My Back Yard – The Advisory Commission on Regulatory

Barriers to Affordable Housing.” Authored by Jack

Kemp and signed by George Bush, Sr., it came to be known

as the “NIMBY REPORT.” The NIMBY Report alleged that

local planning and zoning control

was an impediment to affordable housing

development and had to be challenged (this is the same

position that ABAG / MTC / Plan Bay Area and,

ironically, left-leaning social reformers like the

Marin Community Foundation are advancing today).

But we have to ask ourselves, why would neo-con

Republican politicians propose such a liberal Democratic

sounding idea? Was it because of genuine concern for the

needy? Having personally had a front row seat to watch

the goings on at HUD in Washington, D.C., at the

time, I can say with confidence that it wasn’t. To bring

their ideological motives into relief, we need only swap

the terms “affordable housing development” with “developer profits” and it becomes

clear what the elimination of impediments was all about.

By the early 1990’s, it was obvious that vouchers, Jack

Kemp’s pet program, had failed to increase the

affordable housing supply as promised (without direct

government subsidy contracts, projects no longer

“penciled”). And as the market weakness of the early

1990’s gave way to a new building boom, developers

needed more entitled land - and fast. The NIMBY

Report, a pro-markets,

pro-private developer profits, and pro-big banking

campaign thinly camouflaged as an affordable housing

policy, has been the rallying cry of affordable

housing advocates ever since (who are apparently

oblivious as to its origins).

This pro-development agenda formed the philosophical

basis for the kinds of “straw man” arguments we’re

dealing with today. Resistance to any affordable housing

project in Marin, no matter how ill-conceived, is

immediately labeled NIMBY. But perhaps the

resistance to affordable housing in Marin is less about

NIMBYism than it is about the increasing loss of local

control and community choice in how our communities grow

and cope financially, and how we maintain our quality of

life.

Ownership Will

Save Us?

In 1994, the Government Accounting Office

continued the assault on federally funded housing

programs with a report that damned HUD for its

wastefulness (never mind

that HUD’s total budget was a mere fraction of the U.S.

budgets for defense, farm subsidy, oil subsidy, or other

heavily lobbied line items). Subsequently, a bill was

introduced in the House of Representatives in 1995 to

permanently shut HUD down. It almost passed. Then in

1997, Congress removed the last linchpin of affordable

housing law passed in 1937 that required the federal

government to replace every affordable unit it tore down

or put out of use.

From the mid-1990’s onward, the affordable housing

business remained a shadow of its former self. The new

focus was home ownership, not rentals, probably because

in a “more debt / more leverage” financial system driven

by the lure of lucrative underwriting fees, the mortgage

brokers, banks and investment bankers could “game” that

system more profitably than the rental housing business

(many multifamily funding loopholes were closed after

the S&L crisis).

Then in 2003 Congress passed the “American Dream Down

Payment Initiative” and the already inflating

housing bubble started to expand more rapidly, and

affordability went out the window. We became focused on

the wonders of price appreciation as the solutions to

all our social equity problems. We know how that turned

out.

Bubble-nomics

By 2007, it’s estimated that more than

40 percent of new jobs

being created annually in California were

real estate related

(finance, banking, mortgage underwriting, construction,

materials, real estate sales, household furnishings,

appliances, supporting services, gardeners, house

cleaning and everything they sell at Home Depot). With

stiff environmental regulations dating back to the 1970s

standing in their way and housing demand skyrocketing,

real estate development interests continued to worry

about land scarcity and lengthy entitlement processes.

They needed to “feed the beast.” The California State

Legislature came to their rescue (and has been coming to

their rescue ever since).

“Affordable housing” green-washed with climate change

“concerns” was the perfect argument to defeat opposition

and look like heroes doing it. Following the passage of

AB32 and fueled by the financial backing of

moneyed special interest groups, Senator Darrell

Steinberg crafted

SB375 (drafted in 2005 and signed into law in

September of 2008 just weeks before the crash).

SB375 capitalized on the “NIMBY” argument and

added climate change as a new reason to usurp local

zoning control, even though its claims of greenhouse gas

emissions reductions are unsubstantiated (Appendix

A). With the last obstacles to development swept

away it looked like clear sailing into an endless

building boom. The 2008 crash changed everything.

The unsustainable levels of public and private debt that

fueled the boom have brought on the worst financial

crisis in more than 50 years. Cities that over-extended

themselves by building more and more housing ended up

broke and may never recover (Vallejo, Modesto, Fresno,

Stockton, etc.). The fantasy that building housing

without prerequisite job growth is a path to a better

economic future has been totally discredited. But never

underestimate the power of a bad idea.

Affordable

Housing Today

As it stands today, we really have no cohesive or

financially sustainable national affordable housing

programs. Federal funding assistance for affordable

housing of any kind is pathetically low. Federal Low

Income Housing Tax Credits only offer about $5

billion in annual assistance (Goldman Sachs will pay out

about 3 times that amount this year in executive

bonuses). Section 8 vouchers only cover about 2

million households at a time when the latest census

indicates that 1 in 4 families live at or below the

poverty level. Meanwhile local governments are left to

fight for table scraps as the state and federal

government take more in taxes and fees and give back

less.

Today, we have “in lieu” development where at best we

get 1 or 2 so-called affordable units developed for

every 8 or 9 market rate homes built (about half are for

80 percent median income, which is not all that

affordable). But the negative impacts of these projects

on traffic, infrastructure, tax base, schools, the

environment and everything else far outweigh the

benefits. We occasionally get some projects funded

through grants, but these have been only marginally

successful (e.g., the Mill Valley Fireside

apartments) because the reasons for developing them are

too skewed away from the reality of market economics and

real demand.

We’re told there’s not enough money, that the country

can’t afford it. But that’s only true because our

spending priorities are completely out of whack (i.e.

development of the new F-35 fighter jet is estimated to

cost us $1 trillion dollars over the next decade). In

addition, the affordable housing

development game is now so rigged in favor of large

nonprofit developers that creative private capital is

pretty much excluded. And going forward, private capital

participation will be essential.

What is Our Affordable Housing Problem?

There’s little question that more federal funding

would help provide financial incentives to local

governments and private development interests trying to

address affordable housing challenges. The trickle of

funding available now is just not enough. But before we

start “throwing money” at the “problem” we need to be

sure what we’re trying

to accomplish.

Today’s affordable housing challenges are very different

from the real market demand for housing that followed

the Great Depression and World War II. At that time,

there had been no housing built in decades and there was

a (baby) boom in population and household formation.

Today we have just the opposite.

We have a glut of housing across the state

but much of it is not located

where jobs are. And while traditional jobs are

scarce, many newer jobs go begging because of the lack

of trained candidates in the labor pool. In addition,

net migration in California

is negative: more people are

moving out than moving in.

Marin has experienced stagnant population and jobs

growth over the past 20 years. And

ironically, the Housing Affordability Index is at a

record high. On a tax-adjusted, cash flow basis it’s

never been cheaper to own a home. So where’s the

affordable housing problem?

Our problem today is only similar to the Depression and

its aftermath in that it’s more about economic

dysfunction and our failure to create an equitable

society where real opportunity exists for all. Our

problem is that while corporate profits and CEO

paychecks are at historic highs,

average wages, in real inflation-adjusted terms, have

lagged so far behind the cost of living, and personal

savings are so depleted, that even middle class people

can’t afford to buy a home (much less low income

people). On the other hand, rents are rising because so

little rental housing was built in the past two decades.

So housing options are squeezed for everyone and those

most in need suffer disproportionately.

It’s obvious that unless we address our underlying

social equity and economic problems, there will be no

end to our “housing” problems. But there are still a lot

of things we could be doing at a local level.

What Kinds of Housing Do We Really Need in Marin?

Quotas and mandates have clouded our

thinking. Instead of counting units we should be asking

what types of housing we really need. In many Marin

communities, demographic trends show that we have an

underserved need for many types of affordable housing

that we hear little about in the media. These include:

-

• Housing for

the elderly and assisted living facilities.

• Housing for people with disabilities and special

medical needs.

• Homeless shelters and abused women's safe houses.

• Live/work opportunities like lofts and cooperative

housing.

• Co-housing, where residents design and/or operate

their own hybrid housing solutions (the ultimate in

local control).

• Apartment building preservation, reconfiguration and

substantial rehabilitation.

• Building conversions from commercial to mixed use

residential.

• Sweat equity opportunities where residents can buy

unfinished space to finish out themselves.

• Very small starter rental and condo units for

singles and young couples (as small as 650 sq. ft. two

story).

• Smaller single family housing for the “active

elderly” (partially retired and very active but not

wanting any maintenance obligations).

The list is long. So let’s ask

ourselves, how many of

these kinds of projects are we actually getting built

using our present process?

The answer is none.

The Law of Unintended Consequences

Ironically, the more laws we pass to try to force

zoning changes to enable high density residential

development, the more creative, mixed use / adaptive

use local solutions are “crowded

out” of the market. With our planning tools

(Housing Elements, zoning bonuses, site designation

lists, fast track processing, etc.) radically skewed

to support over- sized, high density in-lieu schemes,

affordable housing development has become a game where

those are the only projects that get considered,

whether or not they make financial sense, community

sense, common sense or there’s any real market demand

for them. Creative capital investors have no incentive

to even try to fill our real housing needs (listed

above) and even if we could get these kinds of

projects built, most wouldn’t be counted as against

our ABAG quotas.

Yet Sacramento’s social engineers and ABAG

planners and some of our elected representatives seem

oblivious to these kinds of

unintended consequences. Residents are

increasingly being bullied into capitulation about

quotas and requirements because they’re told “it’s the

law.” But as anyone who has actually read the

prevailing mishmash of governing laws can attest, the

implementation of “the law” in this case is anything

but clear cut and is open to a variety of

interpretations. And there are certainly enough gray

areas to mount good arguments for

local solutions. But the

problem is that everywhere we look we only seem to be

hearing one interpretation of the law: the one that

most benefits special interests.

It’s fairly obvious that Marin

has many more opportunities for infill, mixed-use

renovation projects with affordable units included

than we do for “high density near public

transportation.” So why aren’t we doing

everything we can to help that happen instead of

continuing to promote unneeded

market rate, in-lieu development?

It’s The Law?

As debates about local planning, Housing Elements,

General Plan updates and affordable housing heat up,

it is increasingly important that the public be given

the full story about what is or is not “the law.” But

this isn’t always the case.

In Mill Valley, for example, the community has been

told for years, by our Planning Department, that we

are required to adopt provisions that provide for

30 units per acre zoning:

our default density for

affordable housing development because we’re

designated an “urban” area by HCD (Housing and

Community Development). This clearly

favors large-scaled development.

This was their justification for recommending approval

of Planned Development (PD), high density

projects on Miller Avenue. These recommendations also

came with a variety of floor area ratio (FAR) bonuses,

and building setback, height and parking variances

because 10 percent of their

units were affordable.

This single issue about site density has been the

basis of endless battles and hundreds of hours of time

at public meetings. It has created enormous community

ill will and it’s even driven some well-intended

affordable housing developers with more modest

schemes, to give up and walk away. But it turns out

that it’s not even true.

According to the HCD Housing Policy Development

regulations on minimum densities for the Housing

Element and the appurtenant regulations, Mill Valley’s

default density is just 20 units per acre not 30. The

regulations state that: "Jurisdictions

(cities/counties) located within a Metropolitan

Statistical Area (MSA) with a population of more than

2 million as listed below (Alameda, Contra Costa, Los

Angeles, Marin, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, San

Diego, San Francisco, and San Mateo - are “urban”)

unless a city / county has a population of less than

25,000” in which case it would be exempt from that

requirement and be governed by the law’s minimums,

which is noted as 20 units per acre.

I suspect the community is dealing with this kind of

thing in other cities in Marin and at the county

level.

For example, op-ed pieces in the Marin IJ

regularly admonish us about our need to comply with

every rule and RHNA allocation that ABAG /

HCD hands us or risk onerous penalties, law suits

and loss of funding. Yet as Carla Condon,

councilmember from Corte Madera, explained in

great detail at a recent

Marin Communities Coalition for Local Control

meeting, this just isn’t true. No city can be

denied funding for which they are otherwise eligible

just because they are in a disagreement with ABAG or

HCD about how

to interpret their legal obligations. A city is only

obligated to create a Housing Element and get it

certified within a specified period of time. And the

kinds of “urban development”

grants that are supposedly at risk have never be

available to small cities in Marin anyway.

Similarly, I’ve read that housing renovation is not

eligible to be counted toward our housing allocation

quota. But again, this turns out not to be the

case. Projects that qualify

as “substantial rehabilitation” can qualify against

ABAG housing mandates (Gov. Code 65583(c)(1)). This

kind of misinformation can discourage private capital

from investing in something we actually need and can

do.

Bottom line: I think the information being given to

the public is grossly inadequate. In fact, getting to

the truth is a full-time undertaking. ABAG has made it

clear they have no intention of answering our

questions (see Mill Valley Patch, 03-28-12,

“Housing Debate Heats Up”). Planning “workshops” and

“community input” sessions for

Plan Bay Area are so tightly orchestrated that

meaningful dialog is completely eliminated. And even

at the local level, I’ve seen our hard working

Planning Commissioners ask staff for clarifications

about the myriad of inter-related affordable housing

regulations only to get explanations that are so

simplistic, so “inside the box” that they only support

the top-down point of view.

All this considered, I wonder sometimes if the fox

isn’t guarding the hen house, or if governing has

gotten so complicated that our planning officials are

just in way over their heads. Either way, who is

looking out for the community’s interests? In the

meantime the only ones who’ve benefited from these

one-sided interpretations of the law are ABAG and

developers promoting new construction projects that

are mostly market rate (i.e. highly profitable)

housing.

I want to make it clear that I have nothing against

profits, and there are some very good nonprofit

organizations that have been building and managing

affordable housing projects in Marin for decades. Many

of these address real demand, like housing for the

elderly and Section 8 tenants. I hope they’re making a

profit so they can continue to do what they do. But

the widely embraced “market rate

+ in-lieu units” approach promoted by the ABAG quota

system (which is primarily profit driven) has

more downside than upside

for the community and it’s not going to get us where

we need to go.

As it stands, by dutifully following mandates from

above we’re giving away the store and getting next to

nothing in return.

A Cycle of

Failure

Our affordable housing challenges go much further

than just getting housing built. In fact, that’s the

easy part. In Part I, I talked about the demise of

Pruitt Igoe, as an

example of a failed affordable

housing concept. And there’s no question that

segregating the poor in isolated

housing developments remains a really bad idea.

But

Pruitt Igoe failed for many other reasons, the

most important of which was the lack of ongoing

funding for maintenance, management, replacement of

fixtures, appliances and equipment, and proper

security.

It’s easy to put up a trophy project (which

Pruitt Igoe was in its day) funded by high

profile, one-time grants and zoning concessions. It’s

easy to have a big party where self-congratulating

politicians and housing advocates show up for photo

ops of shovels being put into the ground. But it’s a

whole other thing to keep that enterprise going for

the long term. It’s a whole other thing to maintain

the buildings year after year, and to work with

families and individuals who live on the edge, day to

day.

The truth is that Priutt Igoe was abandoned by its

creators and left to fend for itself as the fickle

winds of politics shifted to other vote-grabbing

issues, long before it was abandoned by its tenants.

We’re seeing this same story unfold in Marin. A

big fuss is made about the grants that help affordable

projects like the Fireside in Mill Valley get

built. But where will the revenues come from to keep

projects like this operating and well maintained in 10

years? While housing advocates cheer on every new

project proposed, regardless of its merits, the steady

deterioration of our existing affordable housing stock

continues to be a chronic problem. And many existing

Section 8 projects around the county continue

to have disproportionately

higher crime rates and other ongoing management

and maintenance issues that give affordable housing

its bad reputation. These projects continue to need

more operating funds. But where is the effort to

address that need and why aren’t we addressing that

first?

Going forward, who will bear the social and economic

burdens of the future projects driven by

SB375 and the One Bay

Area plan? And just how financially

“sustainable” will the Sustainable Communities

Strategy really be?

As a former affordable housing developer and owner of

large Section 8 housing projects, I can say

unequivocally that these types of projects are much

more management and capital intensive than any other

type of real estate. And when we look at the other

types of affordable housing Marin communities

really need or the demographic we should really be

concentrating on (low and very low income residents),

I don’t see the sources of adequate future revenues to

ensure success. But no one seems to be thinking about

that right now. Affordable housing is just discussed

academically, as if the world were really that simple.

Right now, it’s just “build baby build.”

But wouldn’t it make more sense to work together

locally and regionally to pressure the federal

government to offer better

financing terms to qualified buyers (i.e. 40

year amortized mortgages) so more families could buy

homes? Wouldn’t it make more sense to fight for more

types of financial assistance to

low-income renters and landlords so renters

could afford a better place to live and private

property owners had more financial wherewithal to

renovate and build rental housing than to

waste precious time and money

trying to

re-engineer human behavior and warehouse people in high density

“workforce” housing next to highways?

Making

Better Decisions

One thing I’m sure of is that we’re not going to

solve today’s planning and affordable housing

challenges by continuing to rehash old ideas. More

“business as usual” will just add to our long term

problems. Equally, we’re not going to move forward by

going backwards, dismantling decades of environmental

protections in the name of “streamlining" and “jobs”

and “growth.”

"Environmental" laws like SB375 that pretend to

be one thing but are driven by something else (Appendix

A) are leading to a chain reaction of bad ideas.

For example, the scope of the new “Preferred

Land Use and Transportation Scenario” just

published by the

TAM Executive Committee includes examining “CEQA streamlining opportunities

for development projects as defined by SB375.”

Am I the only one whose head spins from the irony of

all this? Yes, there may be instances of abuses of

environmental protection laws, but name one area of

the law where that’s not true. It’s no justification

for removing protections or not having a thorough

public process.

Things today tend to get reduced to pointless "for" or

"against" arguments. But when it comes to affordable

housing, we need to be asking more substantive

questions about exactly how, where, what kind, why,

when, by what means, to whose benefit and what are the

unexplored alternatives. We need to move the

conversation from the general to the specific. And the

only way to do that is locally. This is the

fundamental purpose of public policy.

Well-crafted

local public policy has to lead our

vision of the future, not consultant’s opinions, not

academic studies, not housing quotas, not a

developer’s bottom line, not special interest groups,

and not a billionaire philanthropist’s pet project.

That’s letting the tail wag the dog and only leads to

knee-jerk decisions and more wasting of public assets,

not lasting solutions.

The kind of process we’re witnessing that

substitutes orchestrated group

workshops and consultant’s studies for

thinking is a recipe

for disaster. I don’t question for a minute the

heartfelt concern and passion of affordable housing

advocates for wanting to correct our world’s social

inequities. But I do question their understanding of

economics and their acumen about the political

horse-trading that’s going on in Sacramento, at

our expense.

But make no mistake about it, the planning challenges

we’re facing today are unlike anything we’ve dealt

with in the past. The world is faster and more

interdependent. Our problems are more complex and our

errors will be more costly. Our environmental

challenges are more precarious than ever before and

many affordable housing development sites that have

traditionally been considered (e.g. sites at or below

sea level) are no longer really viable. We’ve learned

so much about environmental sustainability and human

health in the past 20 years, and the outcry from the

scientific community is so loud and clear, that we can

no longer simplistically equate “building” with

“progress,” or make decisions just for the sake of

short-term economic growth. And we can no longer

justify putting low income or

elderly residents in harm’s way and call it a

solution.

Looking Ahead

We find ourselves in uncharted waters. The

undeniable trend at the state level is the systematic

dismantling of local control. Regional Housing

Needs Assessments, which began decades ago as a

fairly benign way of estimating growth in

California to assist cities in planning for it,

have become a heavy handed, well-funded, quota-driven

system that attempts to wrest

control of local planning

by forcing zoning changes to accommodate high density,

multi-family development (as a condition for

certification of a Housing Element).

I believe this entire system needs to be questioned to

its core.

I remain convinced that the best

affordable housing solutions will come from the

local level, guided by local

policy, informed by local

conditions, needs and markets. There may be

commonalities among the affordable housing solutions

devised by different Bay Area communities and

if so, that’s great. But there certainly aren’t any

solutions that can be applied in all cases, because

Marin, thank goodness, is just too nuanced for

that to work.

As we look ahead toward more equitable housing

solutions, in the words of Apple Computer’s marketing

campaign, I believe we need to “think different.”

The Best Laid Plans - Part IV: Public Policy,

Community Voice & Social Equity

|

“Toto, I don’t think we’re in Kansas

anymore.” ~The Wizard of

Oz

Since the market crash of 2008, real estate

developers, financiers and politicians have been

in panic mode. Though it’s clear that the debt

fueled hyper-growth of the past decades is gone

forever, they remain in deep denial. Like some

neurotic gambler who's lost it all but who’s still

hitting the tables believing he can get it all

back, these powerful interests continue to roll

the dice, regardless of the social and community

costs (quality of life, infrastructure, traffic,

schools, etc.), regardless of the environmental

costs, and regardless of the destabilizing

economic impacts in the long run. The tragedy is

how much damage could be done trying to bring back

the “good old days.”

The concentration of wealth and power at the top

and the influences of special interests are

distorting local planning priorities. As I’ve

tried to illuminate in this series, we can’t

continue to pursue top down central planning

practices or social engineering experiments that

have repeatedly failed in the past. And since “the

market” has not solved all our problems as

promised, and left too many needs unmet, what

should we be doing?

I have no intention of wrapping this all up with a

simplistic “to do” list. I only hope these

articles act as a catalyst for more productive

dialog. Solutions can only start in each

community, each in their own way. But one thing

that is clear is if we want to bring about

effective change, our city and county officials

are going to have to step outside their historical

comfort zones of only looking at issues that are

strictly local. We can no longer divorce ourselves

from the big picture because it’s what is

increasingly driving everything.

It’s true that most city council members are

unpaid volunteers and legitimately complain about

having too big a workload as it is. So it’s hard

enough to get them to cooperate on Marin’s shared

concerns much less problems that have state,

national or international implications. But then

again, planning staff is generally very well paid

and could be doing much more. Isolationism has

worked in the past but we just don’t live in that

world anymore. |

Black Monday; The Crash of

1929 - Library of Congress |

What Is the Problem We’re Trying to Solve?

Marin’s

fundamental disconnect with the ABAG / MTC /

One Bay Area / New Urbanism approach is that

the planning challenges in Marin today are in

many ways the opposite of what the One Bay

Area approach was created to address.

As I’ve said in Part I,

we already have much of what it promises in

terms of sustainability and quality of life.

And Marin’s affordable housing needs are quite

different from most of the other ABAG

communities.

In more urban parts of the Bay Area

(San Francisco, Oakland, Emeryville, San Jose,

etc.) market rate, single family residential

homes are more difficult to build profitably

and average household incomes are lower, but

there are more opportunities to find high

density housing sites. So in those cities it

makes some sense to promote market rate and 80

percent median income housing development in

addition to affordable units.

But in Marin the only thing developers

want to build is single family detached market

rate housing or high end condos so we

shouldn’t have to deal with quotas for that

(or “quotas” at all for that matter). Our

problem is that there is

little we can do to incentivize developers to

build low and very low income housing

and the other types of housing we really need

(see

Part III). Marin’s challenges are

about more than just the size or distribution

of

Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RNHA )

numbers. |

Marin County Housing Needs Allocation, 2007 to

2014

|

Very Low, <50% |

Low, <80% |

Moderate, <120% |

Above Moderate |

Total |

| Belevedere |

5 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

17 |

| Corte Madera |

66 |

38 |

46 |

92 |

244 |

| Fairfax |

23 |

12 |

19 |

54 |

108 |

| Larkspur |

90 |

55 |

75 |

162 |

382 |

| Mill Valley |

74 |

54 |

68 |

96 |

292 |

| Novato |

275 |

171 |

221 |

574 |

1,241 |

| Ross |

8 |

6 |

5 |

8 |

27 |

| San Anselmo |

26 |

19 |

21 |

47 |

113 |

| San Rafael |

262 |

207 |

288 |

646 |

1,403 |

| Sausalito |

45 |

30 |

34 |

56 |

165 |

| Tiburon |

36 |

21 |

27 |

33 |

117 |

| Unincorporated |

183 |

137 |

169 |

284 |

773 |

| Marin Total |

1,095 |