|

|

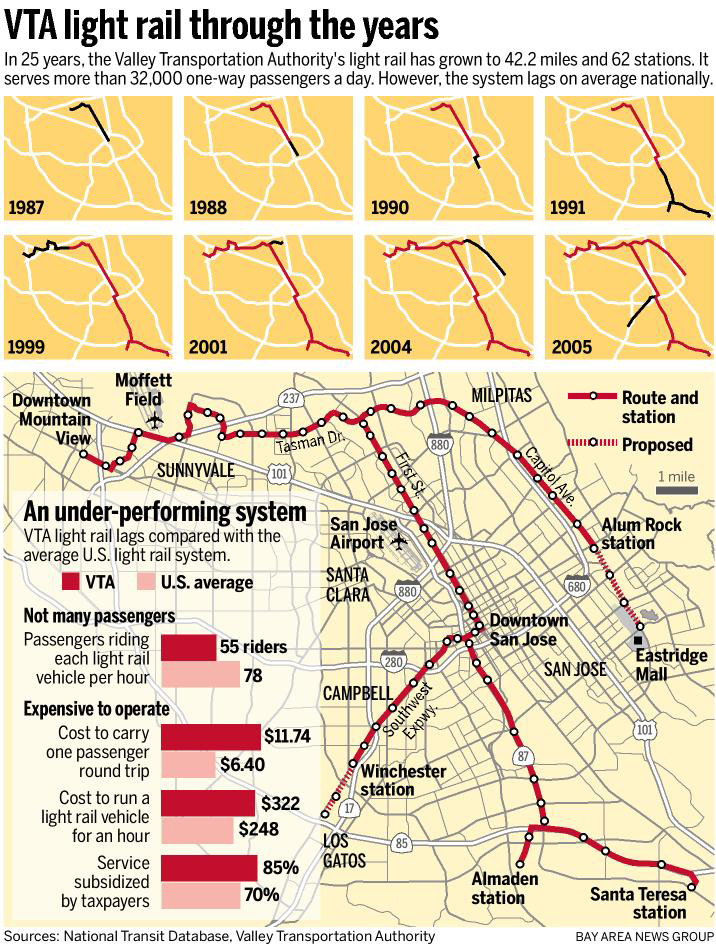

25 years later, VTA light rail among the nation's worstA quarter of a century ago, Santa Clara County's first light-rail train left the station as excited supporters heralded a new wave of state-of-the-art transportation to match the region's burgeoning high-tech industry. But there was no grand celebration this month as Silicon Valley marked 25 years of light rail. The near-empty trolleys that often shuttle by at barely faster than jogging speeds serve as a constant reminder that the car is still king in Silicon Valley -- and that the Valley Transportation Authority's trains are among the least successful in the nation by any metric. Today, fewer than 1 percent of the county's residents ride the trains daily, while it costs the rest of the region -- taxpayers at large -- about $10 to subsidize every rider's round trip. Even light rail's supporters concede the train has not lived up to expectations thus far, but they are optimistic that slow and steady increases in rider counts will continue. "I believe we are ultimately going to realize the (original) vision," said Kevin Connolly, VTA's transportation planning manager. "But I think what's happened is that it wasn't quite as easy or quick as originally conceived of 30 years ago." So what exactly has gone wrong, and what needs to change to make the next 25 years a smoother ride for Silicon Valley's trolley line? Bumpy startThe VTA system, which cost $2 billion to build and $66 million per year to operate, is one of the most inefficient light-rail lines in the nation: The network that officials envisioned in the 1970s and '80s wound up being twice the size, more expensive, less efficient and less popular than first thought. "It is an unmitigated disaster and a waste of taxpayer money," said VTA critic Tom Rubin, a transportation consultant based in Oakland. "I think the original concept was very seriously flawed." Still, light-rail supporters argue the trains have put a dent in Silicon Valley's notoriously nasty freeway traffic, providing more than 32,000 one-way trips each day. For perspective, if all those riders drove on Highway 101 in the South Bay, traffic would increase more than 6 percent. "If we didn't have the current system, we would have terminal gridlock," said the train's godfather, Rod Diridon, a transit advocate who pushed for the network as a county supervisor decades ago.  Reasons are clearStill, VTA light rail has struggled -- and it's mostly because of the valley's sprawl, transportation experts and agency officials say. Connolly noted that the South Bay's first light-rail line was built along onion fields, where planners had expected homes and businesses to pop up along the route. That contrasted with the strategy in most other cities, which is to put light rail along existing, dense corridors. For the most part, the density never materialized in Silicon Valley. As Connolly spoke at VTA headquarters along its main light-rail line on First Street, he noted the orange groves across the street. "In our case we tried to graft a big-city transit type of mode onto a suburban environment, and it's still kind of a work in progress," Connolly said. San Francisco's Muni light-rail system, which carries five times as many passengers as VTA, features dense housing and jobs near stations that riders can walk to, avoiding traffic jams and the huge parking costs. More commuters in the South Bay, on the other hand, stomach awful traffic and record gas prices because the region offers plenty of free parking, and its businesses and homes are spread out. And that's not changing any time soon. "Changing land-use patterns is something that is hard work and takes a long time and a lot of political will. It happens in an incremental way, property by property," said Gabriel Metcalf, executive director of SPUR, a Bay Area planning nonprofit. Riding the railsMany riders say they use light rail because they don't have any other way to get around -- and they like that it's clean, affordable and consistent. "It's very convenient for me," said Mark Vindiola, 47, who takes the train from his home in Milpitas to school and work because he doesn't drive. "I'm happy it's there and I want (the service) to continue." But their main complaint is speed, which is often less than 10 mph in downtown San Jose. "It just takes a while to get through downtown," said Sabrina Baca, 17, as she sat on the train with 18-year-old Fernando Fernandez and their 7-month-old daughter. Asked why they and most people ride the train, the couple said, in unison: "Because they have to." Light rail is generally less economically efficient than long-haul heavy train service such as BART or Caltrain, though San Jose's system is especially feeble. Light-rail agencies in Minneapolis, Houston, Newark, N.J., and Phoenix each run less service than VTA yet carry more passengers than the South Bay's network. Several cities that are much smaller than San Jose -- from St. Louis to Salt Lake City to Portland, Ore. -- also feature light-rail systems with more riders than VTA. Sacramento -- which also opened its light-rail network in 1987, operates with approximately the same level of service and runs through a similarly sprawled-out region -- carries nearly 40 percent more passengers per day than VTA. Connolly pointed out that the Sacramento line has a built-in customer base of state workers who take the line, at a 75 percent discount, to their jobs. The closest VTA has to that: San Jose State students, who make up a large chunk of VTA's riders largely because the line carries students to the university for no additional charge, a cost built into their tuition. Another issue is that San Jose's downtown -- while denser than most parts of Silicon Valley -- is still not the jobs destination seen in the urban cores of other cities. For many riders, it's a place to get through, not to. Future changes coming?Acknowledging the need to improve, the VTA is undergoing a $27 million project to make the service more attractive, largely by adding tracks to launch express trains. VTA is also kicking off an efficiency effort to cut service costs 5 percent, which could help land new grants from the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the Bay Area's transportation agency. Expansions to Los Gatos and East San Jose are also proposed, but those, too, are forecast to attract very few riders and carry large, unfunded capital costs. "In general, we can't lose sight of the fact that we have to do the basics better," Connolly said. "We have to be faster, we have to connect with better destinations." |

|