|

Agenda Item No: 6.d Meeting Date: July 17, 2017

SAN RAFAEL CITY COUNCIL AGENDA REPORT

Department: Finance

Prepared by: Mark Moses,

Finance Director

City Manager Approval:

TOPIC: GRAND JURY REPORT ON FUNDING EMPLOYEE PENSIONS

SUBJECT: CONSIDERATION OF A RESOLUTION APPROVING AND AUTHORIZING THE MAYOR TO

EXECUTE THE CITY OF SAN RAFAEL RESPONSE TO THE MAY 25, 2017 MARIN COUNTY GRAND

JURY REPORT ENTITLED “THE BUDGET SQUEEZE: HOW WILL MARIN FUND ITS PUBLIC

EMPLOYEE PENSIONS?”

RECOMMENDATION: ACCEPT REPORT AND ADOPT RESOLUTION AS PRESENTED

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This staff report provides information about

the Grand Jury Report entitled “The Budget Squeeze: How Will Marin Fund Its

Public Employee Pensions?” and staff’s proposed response. The Report requests a

response from the City for three of the recommendations contained in the report.

BACKGROUND: The 2016-2017 Marin County Grand Jury has issued

its report, dated May 25, 2017 and made public on June 5, 2017, entitled “The

Budget Squeeze: How Will Marin Fund Its Public Employee Pensions?” In this

report, the Grand Jury sought to offer clarity to the issue of funding defined

benefit pensions and encourage public agencies to provide greater transparency

to their constituents.

A

Special Joint City Council Pension-OPEB Subcommittee and City Council Finance

Committee meeting was held on June 6, 2017, at which time the findings,

recommendations and appropriate responses were discussed.

ANALYSIS: Based on the focus of the recommendations, the City

appears to be on track to satisfy the expectations of the Grand Jury with

respect to fiscal management of its pension obligations.

The City of San Rafael does have a relatively high pension

contribution/revenue ratio, and expects that this relationship will continue for

many years. This burden is partially a result of offering retirement benefits

that were competitive with those offered throughout the State. Recent reforms

have resulted in less generous benefits for new employees. The City has

documented its efforts at pension reform at

http://www.cityofsanrafael.org/pension-

retiree-health/ .

In

2011, San Rafael lowered the benefit for new miscellaneous employees from 2.7%

to 2%. It did not lower the benefit rate for new public safety employees, but

reduced their cost of living allowance (COLA) in retirement from 3% to 2%. It

also changed the Final Average Pay used for to calculate the pension benefit

from the last year’s salary to the average of the final three years’ salary.

In 2013, the City further reduced new employee

benefits after the implementation of California’s Public

Employees’ Pension Reform Act (PEPRA). New

miscellaneous employees must wait until age 62 to receive benefits, which

continue to be based on 2% per year times final average pay. For new safety

employees, the rate is now 2.7% instead of 3% while the retirement age has risen

from 55 to 57. Most employees will be eligible for the pre-2011 retirement

benefits for several years to come; however, the City has already experienced

some fiscal relief as new employees have replaced retirees.

Also

contributing to the City’s relatively high annual pension costs is the

aggressive approach its plan administrator, the Marin County Employee Retirement

Agency (MCERA) is taking toward paying down unfunded liabilities. Most plans,

including those administered by CalPERS and other county systems, amortize their

unfunded balances over a period of 30 years; MCERA has implemented a 17-year

amortization period for the largest portion of the liability. More rapidly

amortizing the unfunded liability promotes fiscal sustainability, as it ensures

a more reliable path to fully funding the benefit.

The

City was not directed by the Grand Jury to respond formally to any of the

findings. One finding, F3, asserted that all Marin County agencies will see

significantly higher required pension contributions in the next few years, as a

result of the recent lowering of the discount rates by MCERA, CalPERS and

CalSTRS. The City does not believe that this assertion is accurate with respect

to those agencies under MCERA. MCERA lowered its discount rate from 7.50% to

7.25% for the actuarial valuation as of June 30, 2014. The contributions

associated with this increase have been fully implemented. The current fiscal

year (FY17-18) is the third year for which the new discount rate is being

applied. Thus, the lowering of the discount rate by MCERA will not result in

significantly higher rates in the next few years by the agencies that

participate in its plan. Staff recommends that this be brought to the attention

of the Grand Jury in its response.

The

Grand Jury directed the City to respond to three recommendations, R3, R4 and R8.

Following consultation with the City Council Pension-OPEB Subcommittee and City

Council Finance Committee, staff has prepared the following responses for the

consideration of the full City Council:

R3.

Agencies should publish long-term budgets (i.e., covering at least five years),

update them at least every other year and report what percent of total revenue

they anticipate spending on pension contributions.

Response: The City maintains a three-year forecast for its General Fund, updated

a minimum of twice annually. This forecast includes projected spending on

pension contributions. The City believes that this is sufficient for the purpose

of identifying and funding its pension-related costs.

R4.

Each agency should provide 10 years of audited financial statements and summary

pension data for the same period (or links to them) on the financial page of its

public website.

Response: The City’s website provides links to audited financial statements

going back to the year ended June 30, 2000. Under GASB 68, 10-year pension data

is required to be disclosed in the City’s financial statements as required

supplementary information. Due to the methodology and format changes under GASB

68, the new 10-year history is in the process of being built, with each new

reporting year. FY16-17 will mark the third year that the City reports under

this format.

R8:

Public agencies and public employee unions should begin to explore how

introduction of defined benefit contribution programs can reduce unfunded

liabilities for public pensions.

Response: The existing unfunded liabilities have already been incurred. As such,

new or supplementary programs will not reduce these liabilities. The costs

associated with terminating the current defined benefit

plan would be prohibitive (requiring outlay of hundreds of millions of dollars).

The ability to modify the structure of the plan (e.g., to make room for a

defined contribution plan) would require changes to the statutes that govern

plans under the County Employees Retirement Law of 1937, in addition to

negotiating changes with the affected labor units.

The

City is supportive of any and all legal alternatives that can be negotiated with

labor groups to limit future financial exposure.

ACTION REQUIRED: To comply with the applicable statute, the

City’s response to the Grand Jury report is required to be approved by

Resolution of the City Council and submitted to the Presiding Judge of the Marin

County Superior Court and the Foreperson of the Grand Jury on or before

September 5, 2017. A proposed Resolution (Attachment B) is included that would

approve staff’s recommendation for the City’s response (Attachment C).

RECOMMENDATION: Staff recommends that the City Council adopt

the attached Resolution approving the proposed response to the Grand Jury report

and authorizing the Mayor to execute the response.

ATTACHMENTS:

-

Grand Jury Report “The Budget Squeeze:

How Will Marin Fund Its Public Employee Pensions?” dated May 25, 2017.

-

Resolution

-

Proposed Response (attachment to

Resolution)

2016–2017 MARIN COUNTY CIVIL GRAND JURY

The Budget Squeeze

How Will Marin Fund Its Public Employee Pensions?

Report Date:

May 25, 2017

Public Release Date: June 5, 2017

Marin County

Civil Grand Jury

The Budget Squeeze

How Will Marin Fund Its Public Employee Pensions?

SUMMARY

Twenty years ago, the only people who cared about public employee pensions

were public employees. Today, taxpayers are keenly aware of the financial

burden they face as unfunded pension liabilities continue to escalate. The Grand Jury estimates that the unfunded liability for

public agencies in Marin County is approximately $1 billion.

In 2012, the state passed the California Public Employees’ Pension Reform Act

of 2013 (PEPRA), which reduced pension benefits for new employees hired after

January 1, 2013. PEPRA was intended to produce a modest reduction in the

growth rate of these obligations but it will take years to realize the full

impact of PEPRA. In the meantime, pension obligations already accumulated are

undiminished.

This report will explore several aspects of this issue:

It’s Worse than You Thought – While a net pension liability of

$1 billion may be disturbing, the true economic measure of the obligation is

significantly greater than this estimate.

The Thing That Ate My Budget – The annual expense of funding

pensions for current and future retirees has risen sharply over the past

decade and this trend will continue; for many agencies, it is likely to

accelerate over the next five years. This will lead to budgetary squeezes.

While virtually every public agency in Marin has unfunded pension obligations,

some appear to have adequate resources to meet them, while many do not. We

will look at what agencies are currently doing to address the issues and what

additional steps they should take.

The Exit Doors are Locked – Although there are no easy solutions, one

way to reduce and eliminate unfunded pension liabilities in future years would

be transitioning from the current system of defined benefit pension

plans to defined contribution pension plans, similar to a 401(k).

However, this approach is largely precluded by existing statutes and made

impractical by the imposition of termination fees by the pension funds that

manage public agency retirement assets.

The Grand Jury’s aim is to offer some clarity to a complex issue and to

encourage public agencies to provide greater transparency to their

constituents.

BACKGROUND

Defined benefit pension plans are a significant component of public employee

compensation. These plans provide the employee with a predictable future

income stream in retirement that is protected by California Law.1 However, the promise made by an employer today creates a

liability that the employer cannot ignore until the future payments are due.

The employer must contribute and invest funds today so that future obligations

can be met when its employees retire. Failing to set aside adequate funds or

investing in underperforming assets results in a funding gap often referred to

as an unfunded pension liability. In order to be consistent with

Governmental Accounting Standards Board’s (GASB) terminology, this paper will

refer to the funding gap as the Net Pension Liability (NPL).

Actuaries utilize complicated financial models to estimate the Total

Pension Liability, the present value of the liabilities resulting from

pension plan obligations. Pension plan administrators employ sophisticated

asset management strategies in an effort to meet targeted returns required to

fund future obligations. Nevertheless, the logic behind pension math can be

summed up in a simple equation: Total Pension Liability (TPL) - Market

Value of Assets (MVA)

= The Net Pension Liability (NPL). The NPL represents the funding gap between

the future obligations and the funds available to meet those obligations.

Conceptually, it is an attempt to answer the question: “How much would it be

necessary to contribute to the plan today in order to satisfy all existing

pension obligations?”

California is in the midst of an active public discussion about funding the

retirement benefits owed to public employees. These retirement benefits have

accumulated over decades and are now coming due as an aging workforce feeds a

growing wave of retirements. The resulting financial demands will place stress

on the budgets of public agencies and likely lead to reduced services,

increased taxes or both.

The roots of the current crisis in California stretch back to the late 1990’s,

when the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) held assets

well in excess of its future pension obligations. The legislature approved and

Governor Davis signed SB 400, which provided a retroactive increase in

retirement benefits and retirement eligibility at earlier ages for many state

employees. These enhancements were not expected to impose any cost on

taxpayers because of the surplus assets held by the retirement fund. However,

the value of those assets fell sharply as a consequence of the bursting of the

dotcom bubble in the early 2000s and the Great Recession

starting in 2008. (CalPERS suffered a 24% decline in the value of its holdings

in 2009 alone.2)

Where there had been surplus assets, the state now has large unfunded

liabilities.

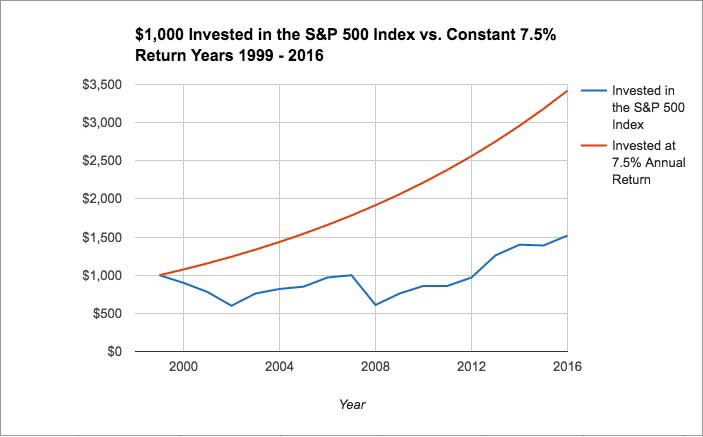

The following graph illustrates the problem. If you had invested $1,000 in

1999, when the decision to enhance retirement benefits was made, and received

a return of 7.50% annually — a

1 “California Public Employee

Retirement Law (PERL) January 1, 2016.” CalPERS.

2 Dolan, Jack. “The Pension Gap.”

LATimes.com. 18 Sept. 2016.

commonly used assumption of California’s pension fund administrators — your

investment would have grown to about $3,500 by the end of 2016. By contrast,

had you received the returns of the S&P 500 over that same period, you would

have only about $1,500, less than half of what had been assumed.

Last year, Moody’s Investors Service reported that the unfunded pension

liabilities of federal, state and local governments totaled $7 trillion.3 Closer to home, the California Pension Tracker, published

by the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research, places the state’s

aggregate unfunded pension liability at just under $1 trillion.4

Marin has not been exempt. Recent published estimates put the NPL for public

agencies in Marin at about $1 billion. This is confirmed by our research.

The vast majority of employees of public agencies in Marin are covered by a

pension plan. Three agencies administer these plans:

-

California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS),

a pension fund with $300 billion in assets that covers employees of many

public agencies, excluding teachers.

-

California State Teachers Retirement System (CalSTRS),

a pension fund with $200 billion in assets that covers teachers.

-

Marin County Employees’ Retirement Agency (MCERA),

a pension fund with $2 billion in assets that provides services to a number

of Marin public agencies, the largest being the County of Marin and the City

of San Rafael.

3 Kilroy, Meaghan,. “Moody’s: U.S. Pension

Liabilities Moderate in Relation to Social Security, Medicare.” Pension &

Investments. 6 April 2016.

4 Nation, Joe. “Pension

Tracker.” Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

Accessed 5 March 2017.

The Grand Jury chose to address public employee pensions not because it is a

new problem, but because it is so large that it is likely to have a material

future impact on Marin’s taxpayers, its public agencies and their employees.

METHODOLOGY

The Grand Jury chose to review and analyze the audited financial statements

of the 46 agencies included in this report for the fiscal years (FY)

2012-2016 (see Appendix B, Methodology Detail). We captured a snapshot of

the current financial picture as well as changes over this five- year

period. In addition to reviewing net pension liabilities and yearly

contributions of each agency, we collected key financial data from their

balance sheets and income statements. We present all of this data both

individually and in aggregate in the appendices.

The agencies were organized into three main types: municipalities, school

districts and special districts. The special districts were further

separated into safety (fire and police) and all other, which includes

sanitary and water districts and the Marin/Sonoma Mosquito and Vector

Control District. Evaluating the agencies in this way provided insight into

which types of agencies were most impacted by pensions. Comparing agencies

within those designations provided further clarity on which agencies may

need to take specific action sooner rather than later. The school districts,

which have some unique characteristics, require a separate discussion.

Financial Data and Standards

The Grand Jury analyzed data from the Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports

(CAFR), Audited Financial Reports and actuarial reports from the pension

fund administrators.

The Grand Jury analyzed the annual reports for each agency for the five

fiscal years 2012 through 2016. A listing of the financial reports upon

which the Grand Jury relied is presented in Appendix A, Public Sector

Agencies.

Additional scrutiny was paid to the fiscal years 2015 and 2016 due to

reporting changes required by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB),5 described in detail later in this report. For further

information, see Appendix C.

The Grand Jury interviewed staff and management from selected public

agencies and selected pension fund administrators.

The Grand

Jury reviewed current law related to pensions.

Our

investigation was to determine only the pension obligations of each agency.

The Grand Jury

5 “GASB 68.”

Governmental Accounting Standards Board.

did not attempt to analyze the details of individual pension plans for any

of the public agencies. The Grand Jury did not analyze the mix of pension

fund investments; the investments for each public agency are managed by the

appropriate pension fund according to standards and objectives established

by that fund as contracted by their customers.

The Grand Jury did not investigate other employee benefits such as deferred

compensation or inducements to early retirement.

Financial Data Consistency

The following agencies did NOT publish audited financial reports for FY 2016

in time for the Grand Jury to include those financial data in this report:

-

City of Larkspur

-

Town of Fairfax

-

Central Marin Police Authority

The lack of a complete set of financial data for the fiscal years under

investigation is reflected in this report in the following ways:

The financial tables below include an asterisk (*) next to the name of

agencies for which financial data is missing. Table cells with data which is

Not Available are marked as N/A.

Summary financial data totals do not include data for missing agencies for

FY 2016. Percentages presented are calculated only with available data.

One agency, the Central Marin Police Authority (CMPA), presents other

complications. The predecessor agency of CMPA, the Twin Cities Police

Authority (TCPA), was a Joint Powers Authority of the City of Larkspur and

the Town of Corte Madera. Subsequent to the publication of the TCPA FY 2012

audit report, a new Joint Powers Authority was created consisting of the

former TCPA members plus the Town of San Anselmo. Thus, a strict comparison

of financial condition over the full five year term of this report is not

possible. The FY 2012 audit report for TCPA is included in the CMPA

statistics as the predecessor agency.

DISCUSSION

It’s Even Worse than You Thought

The Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB) establishes accounting

rules that public agencies must follow when presenting their financial

results. The recent implementation of GASB Statement 68 requires public

agencies to report NPL as a liability on the balance sheet in their audited

financial statements beginning with the fiscal year ended June 30, 2015.6 Prior to this accounting rule change, agencies only

reported required yearly contributions to pension plans on the income

statement, but NPL was not reflected on the balance sheet. The new method of

reporting has provided greater transparency into the future impact of

pension promises on current agency financials.

The addition of NPL as a liability on the balance sheet of government

agencies has resulted in dramatic reductions to most agencies’ net

positions. The net position (assets minus liabilities, which is referred

to as net worth in the private sector) is one metric used to evaluate the

financial health of an organization. In the private sector, when net worth

is negative, a company is considered insolvent, which is a signal to the

investment community of potential financial distress. During the course of

our research, the Grand Jury discovered many agencies that now have negative

net positions following the addition of NPL to their balance sheets. We will

discuss the possible implications of this new reality in the section

entitled The Thing That Ate My Budget.

The calculation of the NPL involves complex actuarial modeling including

many variables. Specific to each agency are the number of retirees, the

number of employees, their compensation, their age and length of service,

and expected retirement dates. Also included in the evaluation are general

economic and demographic data such as prevailing interest rates, life

expectancy and inflation. Actuaries base their assumptions on statistical

models. But these assumptions can change over time as economic or

demographic conditions change, which make regular updates to actuarial

calculations essential. The total of all present and future obligations is

calculated based on these assumptions. A discount rate is then applied to

calculate the present

value of the obligations and account for the time value of money.7 This calculation yields the

Total Pension Liability (TPL). Put simply, the total pension liability is

the total value of the pension benefits contractually due to employees by

employers.

Agencies are required to make annual contributions to the pension plan

administrator. A portion of the yearly contributions is used to make

payments to current retirees and a portion is invested into a diversified

portfolio of stocks, bonds, real estate and other investments. The

investments are accounted for at market value (i.e. the current market price

rather than book value or acquisition price.) In the calculation of NPL, the

value of this investment portfolio is referred to

6 “GASB 68.”

Governmental Accounting Standards Board

7 See Appendix C

as Market Value of Assets (MVA). Consequently the NPL = TPL - MVA. The net

pension liability is simply the difference between how much an entity should

be saving to cover its future pension obligations and how much it has

actually saved.

Although the NPL calculation depends on many variables, it is extremely

sensitive to changes in the discount rate, the rate used to calculate the

present value of future retiree obligations.8 The

discount rate has an inverse relationship to the net pension liability (i.e.

the higher the discount rate, the lower the NPL). GASB requires pension plan

administrators to use a discount rate that

reflects either the long-term expected returns on their investment

portfolios or a tax-exempt municipal bond rate.9 It

is common practice for government pension administrators to choose the

higher discount rates associated with the expected return on their

investment portfolios.

Choosing the higher discount rate produces a lower NPL, which requires lower

contributions from agencies today with the expectation that investment

returns will provide the balance. While a portfolio mix that contains stocks

and other alternative assets might produce a higher expected return, these

portfolios are inherently more risky and will experience significantly more

volatility, potentially leading to underfunding of the pension plans.

Until recently, the three pension administrators (CalPERS, CalSTRS and MCERA)

that manage the assets on behalf of all of Marin’s current employees and

retirees used discount rates between 7.50% and 7.60%. Prolonged weak

performance in financial markets has resulted in the long- term historical

returns of pension funds falling below the discount rate. For example,

CalPERS 20-year returns dropped to 7.00% following a few years of very poor

investment performance, falling under the 7.50% discount rate.10 In response, CalPERS announced in December 2016 that

it would cut its discount rate to 7.00% over the course of the next three

years.11 CalSTRS will cut its rate first to 7.25%

and then to 7.00% by 2018.12 In early 2015, MCERA

cut its discount rate from 7.50% to 7.25%. As noted before, a lower discount

rate results in a higher NPL. A higher NPL leads to increasing yearly

contributions. So you see, it’s worse than you thought. But keep reading,

because it may be even worse than that.

Discount

rates may yet be too high even at the new, lower 7.00-7.25% range.

At this point, it is helpful to provide some historical context. The

risk-free rate,13 typically the US 10-Year Treasury

note, yielded 2.37% as this report is written. (Real-time rates are

available on Bloomberg.com.14) US Treasury

securities are considered risk free because the probability of

8 “Measuring Pension Obligations.”

American Academy of Actuaries Issue Brief. November 2013, pg 1

9 “GASB 68.”

Government Accounting Standards Board

10 Gittelsohn, John. “CalPERS

Earns 0.6% as Long-Term Returns Trail Fund’s Target.”

Bloomberg.com. 18 July 2016.

11 Pacheco, Brad and Davis, Wayne and White, Megan.

“CalPERS to Lower Discount Rate to Seven Percent Over the

Next Three Years.” CalPERS.ca.gov. 21

Dec. 2016.

12 Myers, John. “California

Teacher Pension Fund Lowers its Investment Predictions, Sending a Bigger

Invoice to State Lawmakers.” LA Times.com.

1 Feb. 2017.

13 “Risk Free Rate of Return.” Investopedia.com

14 “Treasury Yields.”

Bloomberg.com

default by the US government is considered to be zero. Investment returns in

the range of 7.00%

-

8.00% were attainable with little volatility

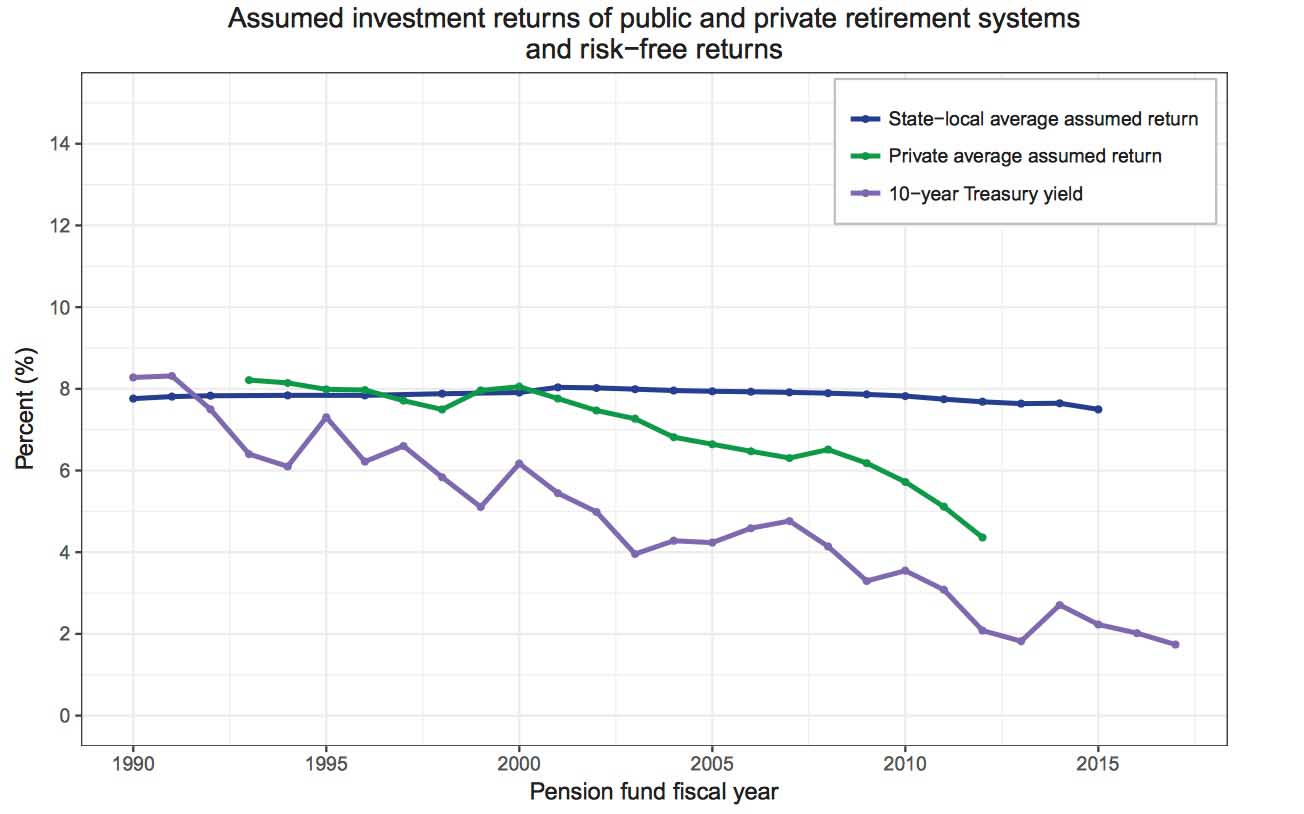

in the past because the risk-free rate was much higher. Between 1990 and

2016, risk-free rates have declined substantially, by around six

percentage points.15 Discount rates in public

sector pension plans have not declined proportionally. The following chart

illustrates how the public sector has failed to reduce its assumed rates

of return in response to the decline in risk-free rates.

From: “The Pension Simulation Project: How Public Plan Investment

Risk Affects Funding and Contribution Risk.”

Rockefeller Institute. Accessed on 23 March 17. pg.3.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, central banks around the

world engaged in the artificial support of lower interest rates through

quantitative easing to boost global growth.16

Record-low interest rates followed, with interest rates on some sovereign

debt even falling into negative territory. While easy monetary policy

aided in spurring global growth, the prolonged

period of low interest rates and weak investment returns has contributed

to the dramatic underfunding of pension plans around the world.

15 Boyd, Donald J. and Yin, Yimeng. “How Public Pension Plan Investment Risk Affects Funding and

Contribution Risk.” The Rockefeller Institute of Government

State University of New York. Jan. 2017.

16 Martin, Timothy W. and Kantchev, Georgi and Narioka,

Kosaku. “Era of Low Interest Rates Hammers

Millions of Pensions

Around World.” WSJ.com 13 Nov. 2016.

Pension plans in the private sector have lowered their discount rates in

tandem with declining yields in the bond market. The Financial Accounting

Standards Board (FASB) is the accounting rule-maker for for-profit

corporations. FASB takes the view that, because there is a contractual

requirement for the plan to make pension payments, the rate used to

discount them should be comparable to the rate on a similar obligation.

FASB Statement 87 says, “...employers may also look to rates of return on

high-quality fixed-income investments in determining assumed discount

rates.”17 The effect is that pension obligations

in the private sector are valued using a

much lower discount rate than those used in the public sector. We looked

at the ten largest pension funds of US corporations. Based on their 2015

annual reports, the average discount rate on pension assets was 4.30%.18

A significant body of research written by economists, actuaries and policy

analysts has been devoted to the topic of whether discount rates used in

public sector pensions are too high. Some suggest that the FASB approach

is more appropriate, others believe the risk-free rate should be used, while still others contend that the current approach

is perfectly reasonable. The Grand Jury cannot opine on which is the best

and most accurate approach. Our research can only illuminate the financial

impact of lower discount rates on Marin County agencies.

An additional reporting requirement of GASB 68 is the calculation of the

NPL using a discount rate one percentage point higher and one percentage

point lower than the current discount rate in order to show the

sensitivity of the NPL to this assumption. The current financial

statements reflect the following rates, which, due to the recent discount

rate reductions noted above, are already outdated:

|

Pension Fund |

Discount Rate |

+ 1 Percentage Point |

-1 Percentage Point |

|

CalPERS |

7.50% |

8.50% |

6.50% |

|

CalSTRS |

7.60% |

8.60% |

6.60% |

|

MCERA |

7.25% |

8.25% |

6.25% |

Because of this new disclosure requirement, the Grand Jury compiled the

NPLs of the agencies at a discount rate range of between 6.25% - 6.60%.

The individual results are presented in Appendix E; the total amount for

the Marin agencies included in this report is $1.659 billion.

In this discussion, we have focused on the risk of lower rates of return,

but there is a possibility that investment returns could exceed the

discount rates assumed by the pension administrators.

17 “Statement of Financial

Accounting Standards No. 87, Employers’ Accounting for Pensions”

Financial Accounting Standards Board. paragraph 44.

18 See Appendix F

However, this possibility appears to be unlikely in that it would

constitute a dramatic reversal of a decades-long trend. (See graph on page

7.) If that occurred, the effect would be lower NPLs and lower required

contributions by employers. Regardless of investment returns, employers

would still be required to make some contributions.

While the discussion of growing NPLs and lower discount rates may seem

abstract, ultimately they lead to higher required contributions by public

agencies to their pension plans. Because these payments are contractually

required, they are not a discretionary item in the agency’s budgeting

process. Consequently, steadily increasing pension payments will squeeze

other items in the budget. In the next section, we discuss the impact on

Marin’s public agencies’ budgets.

The Thing That Ate My Budget

A budget serves the same purpose in a public agency as it does in a

for-profit enterprise or a household. It is a statement of priorities in a

world of finite resources. As growing pension expenses demand an

increasing share of available funding, agencies must figure out how to

stretch and allocate their resources.

This budgetary conundrum is not unique to Marin. A recent article in the

Los Angeles Times19 discusses what can

happen at the end stage of rising pension expenses. The City of Richmond

has laid off 20% of its workforce since 2008 and projects pension expenses

rising to 40% of revenue by 2021.

The explosion of pension expenses played a key role in three California

cities that have filed for bankruptcy protection since 2008: Vallejo,20 Stockton,21 and San

Bernardino.22 Several factors played a role in

these California bankruptcies. In the case of Vallejo, booming property

tax revenues during the real estate bubble led city officials to offer

generous salary and benefit

increases. Property taxes plummeted after a wave of foreclosures during

the financial crisis and city officials could not cut enough of the budget

to meet obligations. In particular, the city’s leadership was unable to

negotiate cuts to pension benefits. This lack of flexibility forced

Vallejo into bankruptcy. Further threats of litigation from CalPERS during

the bankruptcy process kept the City from negotiating cuts to pension

benefits as part of its bankruptcy plan. Despite exiting bankruptcy,

Vallejo remains on unstable financial footing. Stockton and San Bernardino

have similar stories: overly generous salary and benefits offered during

boom times, some fiscal mismanagement (i.e. ill-timed bond offerings,

failed redevelopment plans, etc.) followed by the inability to cut

benefits when revenues declined.

19 Lin, Judy. “Cutting jobs,

street repairs, library books to keep up with pension costs.”

Los Angeles Times 6 Feb. 2017.

20 Hicken, Melanie. “Once

bankrupt, Vallejo still can’t afford its pricey pensions.”

Cnn.com 10 March 2014.

21 Stech, Katie. “Stockton

Calif., To Exit Bankruptcy Protection Wednesday.” WSJ.com 24

Feb. 2015.

22 Christie, Jim. “Judge

Confirms San Bernardino, California’s Plan to Exit Bankruptcy.”

Reuters.com 27 Jan 2017.

In budgeting for pension expense, agencies have two types of contributions

to consider: the Normal Cost and the amortization of the NPL. The

Normal Cost is the amount of pension benefits earned by active employees

during a fiscal year. In addition, agencies must make a payment toward the

NPL. A pension liability is created in every year the fund’s investments

underperform the discount rate. The liability for each underfunded year is

typically amortized over an extended period, which may be as long as 30

years.

While the passage of PEPRA has reduced the Normal Cost somewhat, the

payments needed to amortize the NPL have been rising and will continue to

rise in the coming years. This trend will only be exacerbated by the

recent decisions of CalPERS and CalSTRS to lower their discount rates. In

this section, we will discuss the stress this is placing on the budgets of

Marin public agencies.

Revenues of public agencies come from defined sources, including property

taxes, sales taxes, parcel taxes, assessments and fees for services. Cash

flow may be supplemented by the issuance of general obligation bonds, but

these require repayment of principal along with interest.

The budgeting process of public agencies is not always transparent.

Although final budgets are made public, the choices made along the way —

specifically, which spending priorities did not make it into the final

budget — are usually not disclosed.

In 2016, the Marin/Sonoma Mosquito and Vector Control District

commissioned a study of the district’s financial situation over a

projected ten-year time frame, which concluded:

In addition to the basic level of incurred and approved expenditures

modeled .., the District has long term pension liabilities. Budgets have

been reduced in recent years, but without additional revenues, the

District would be forced to implement severe cutbacks in services and

staffing.23

The report concludes that expenses will exceed revenues beginning in FY

2018, with a deficit widening through FY 2027, the final year of the

study, and that the district’s reserves will be exhausted by FY 2024.

The Grand Jury commends the district for taking the responsible step of

investigating its future financial obligations. We believe that a long

term budgeting exercise — whether done internally or by an outside

consultant — should be completed and made public by every agency every few

years.

The Grand Jury chose several balance sheet and income statement items to

provide context in calculating the relative burden that pension

obligations placed on each agency. We felt a more

23 Cover letter from NBS to the Board of Trustees and

Phil Smith, Manager, Marin/Sonoma Mosquito Vector Control District dated

November 9, 2016.

meaningful analysis could be gleaned from examining ratios rather than

absolute numbers. For example, the $48 million dollar pension contribution

that the County made in 2016 might sound less shocking when presented as

8% of the county’s revenues. The County’s $203 million NPL might be

perceived as extraordinary, but not necessarily so when presented with a

balance sheet that held $400 million in cash.

We focused on two metrics: 1) The percentage of revenue spent on pension

contributions each year over a five-year period, and 2) The percentage of

NPL to cash on the balance sheet to for fiscal years 2015 and 2016. The

first metric was an attempt to answer the question of how much of an

agency’s budget is spent on yearly pension contributions. The second

metric addressed the question of whether an agency had financial resources

to pay down pension liabilities in order to reduce their future yearly

contributions.

The recent announcements of discount rate reductions at both CalPERS and

CalSTRS will lead to increases in NPL, resulting in increasing

contributions for their participating agencies. As CalPERS and CalSTRS

have not yet implemented the discount rate reductions, the financial

statistics we have used in the following discussion do not reflect these

pending increases and, therefore, somewhat understate the budgetary

impact.

Given the wide scope of public missions, responsibilities and funding

sources of the agencies investigated in this report, it is not easy to

generalize about the consequences of budgetary shortfalls for individual

agencies. However, we found similarities among agencies with similar

missions.

School

Districts

School districts share many characteristics: They are included in a single

pool (i.e., identical contribution rates for all districts) for both

CalSTRS and CalPERS; they have similar missions and similar financial

structures and are, therefore, homogeneous. This is the only category

where the agencies contribute to two pensions administrators: CalSTRS for

certificated employees and CalPERS for classified staff. Both CalSTRS and

CalPERS place eligible school-district employees into a single pool for

purposes of determining the annual required contribution.

Consequently, we see that pension contributions as a percentage of revenue

are fairly consistent across districts.

|

School District |

FY 2016 |

FY 2015 |

FY 2014 |

FY 2013 |

FY 2012 |

|

Bolinas-Stinson Union School District |

6.2% |

5.1% |

5.3% |

4.4% |

5.0% |

|

Dixie Elementary School District |

5.8% |

5.7% |

5.2% |

5.4% |

5.3% |

|

Kentfield School District |

5.4% |

5.2% |

4.9% |

4.9% |

5.1% |

|

Larkspur-Corte Madera School District |

5.5% |

5.3% |

5.0% |

4.6% |

5.0% |

|

Marin Community College District |

5.8% |

6.0% |

4.7% |

3.9% |

3.6% |

|

Marin County Office of Education |

3.3% |

2.9% |

2.8% |

2.8% |

2.7% |

|

Mill Valley School District |

5.1% |

4.8% |

4.4% |

4.5% |

4.8% |

|

Novato Unified School District |

4.4% |

4.4% |

4.9% |

4.8% |

4.8% |

|

Reed Union School District |

5.2% |

4.8% |

4.7% |

4.6% |

4.4% |

|

Ross School District |

5.0% |

4.7% |

4.6% |

4.6% |

4.3% |

|

Ross Valley School District |

5.5% |

5.1% |

4.8% |

4.8% |

4.6% |

|

San Rafael City Schools - Elementary |

4.6% |

4.4% |

4.1% |

4.1% |

4.0% |

|

San Rafael City Schools - High School |

5.3% |

4.8% |

4.4% |

4.5% |

4.4% |

|

Sausalito Marin City School District |

3.4% |

3.7% |

3.3% |

3.0% |

2.7% |

|

Shoreline Unified School District |

4.9% |

5.0% |

5.0% |

3.8% |

4.1% |

|

Tamalpais Union High School District |

5.7% |

4.6% |

4.9% |

5.0% |

4.9% |

|

Total |

5.0% |

4.7% |

4.5% |

4.3% |

4.3% |

| |

< 5% |

|

5% - 10% |

|

10% - 15% |

|

> 15% |

Pension contributions as a percentage of revenue for Marin’s school

districts have increased from 4.3% in FY 2012 to 5.0% in FY 2016.

Increases will continue over the next five years, but at a much higher

rate. CalSTRS contribution rates are governed by law and, under AB 146924, contribution rates are scheduled to increase from

10.73% of certificated payroll in FY 2016 to 19.10% in FY 2021 (and remain

at that level for the next 25 years), an increase of 78%.25 For classified employees, the CalPERS contribution

rates will be increasing from 11.847% of payroll in FY 2016 to 21.50% in

FY 2022, an increase of over 81%.26 This implies

that school districts will be spending 9% of their revenues on pension

contributions within the next five years.

24 AB-1469 State teachers’ retirement: Defined Benefit

Program: funding., California Legislative

Informative

25 “CalSTRS Fact Sheet, CalSTRS

2014 Funding Plan.” CalSTRS. July 8, 2014.

26 “CalPERS Schools Pool

Actuarial Valuation as of June 30, 2015.” CalPERS. April 19,

2016.

School districts are already running on tight budgets, with the average

Marin school district expenses having slightly exceeded revenues in fiscal

year 2016. Thus, increases in outlays for pensions will necessitate

service reductions, tax increases or a combination of the two.

Many of the school districts have General Obligation (GO) bonds

outstanding, which contributes to their precarious financial position.

With the recent addition of NPL to their balance sheets, most of the

school districts have negative net positions. As discussed earlier, in the

private sector a negative net position is considered a sign of financial

distress and possible insolvency. When we asked whether the rating

agencies had expressed concerns or threatened to downgrade their existing

debt, the responses from several districts were that they had no

difficulties refinancing their bonds and had all maintained their high

credit ratings.

The Grand Jury found this particular issue perplexing. A healthy balance

sheet is essential in the private sector to attaining a high credit

rating. We learned, however, that this is not how rating agencies view a

Marin County agency’s credit worthiness. In addition to looking at a

particular agency’s financials, the rating firms also evaluate the

likelihood of getting paid back in the event of a default from other

resources, more specifically Marin taxpayers. GO bonds have a provision

where, in the event of a shortfall or default on a bond, the agency can

direct the tax assessor to

increase property taxes to satisfy the obligation.27

Consequently, a rating agency is really

assessing the ability to collect directly from Marin County taxpayers.

Given Marin’s relatively high home values and incomes, collection from

Marin taxpayers is a safe bet in the eyes of the rating agencies, thereby

making it completely defensible to assign a AAA rating on a GO bond from

an agency with a negative net worth. Thus, taxpayers, and not bondholders,

bear the risk of an individual agency’s insolvency.

Another concern for school districts is their reliance on parcel taxes to

supplement revenue. Most Marin school districts have parcel taxes, which

run as high as 20% of revenue in some districts and average 9.7%.28 This important source of revenue is subject to

periodic voter approval and requires a two-thirds vote to pass.

Historically, parcel tax measures have seldom failed in Marin. In November

2016, both Kentfield and Mill Valley had ballot measures to renew existing

parcel taxes. Kentfield failed to get the required two-thirds and Mill

Valley’s measure barely passed.

This raises two concerns: 1) that parcel tax measures will face greater

opposition if voters believe the money is going for pensions; and 2) that

districts’ already tight finances will be substantially worsened if this

source of funding is reduced.

27 “California Debt Issuance

Primer Handbook.” California Debt and Investment Advisory

Commission. pg 134.

28 Sources: parcel tax data from ed-data.org, revenue

data from audit reports (see Appendix A)

|

K-12 School District |

Parcel Tax Revenue as % of Total Revenue |

|

Bolinas-Stinson Union School District |

13.3% |

|

Dixie Elementary School District |

7.6% |

|

Kentfield School District |

20.0% |

|

Larkspur-Corte Madera School District |

11.9% |

|

Mill Valley School District |

20.0% |

|

Novato Unified School District |

4.4% |

|

Reed Union School District |

8.6% |

|

Ross School District |

8.9% |

|

Ross Valley School District |

12.5% |

|

San Rafael City Schools - Elementary |

4.4% |

|

San Rafael City Schools - High School |

7.0% |

|

Sausalito Marin City School District |

0.0% |

|

Shoreline Unified School District |

6.2% |

|

Tamalpais Union High School District |

10.2% |

|

Average |

9.3% |

Given these budget pressures, it is difficult to imagine how the impact of

increasing pension contributions will not ultimately be felt in the

classroom.

Municipalities & the County

The County and the 11 towns and cities in Marin County (we will refer to

them collectively as the “municipalities”) have broad responsibilities.

Within this group, however, there are important differences. Populations

differ widely, from Belvedere at about 2,000 to San Rafael at 57,000. In

some municipalities, police and/or fire protection services are provided

by a separate agency. In others they fall under the municipality’s

auspices. These factors lead to some variation among this category.

Unlike school districts, municipalities (and special districts, which we

will discuss next) have individualized schedules for amortization of their

NPLs. Although we can make overall statements about recent and expected

increases in pension expense, there can be substantial variation among

jurisdictions.. The following table shows the pension contribution as a

percent of revenue for each municipality over the past 5 years.

|

Municipality |

FY 2016 |

FY 2015 |

FY 2014 |

FY 2013 |

FY 2012 |

|

City of Belvedere |

4.2% |

3.8% |

3.9% |

5.2% |

5.7% |

|

City of Larkspur* |

N/A |

3.8% |

5.0% |

6.0% |

7.0% |

|

City of Mill Valley |

6.4% |

5.5% |

5.2% |

5.1% |

6.3% |

|

City of Novato |

5.4% |

5.2% |

9.1% |

8.4% |

8.3% |

|

City of San Rafael |

19.2% |

18.8% |

18.8% |

15.9% |

16.8% |

|

City of Sausalito |

6.6% |

9.7% |

6.9% |

10.8% |

12.3% |

|

County of Marin |

7.9% |

6.9% |

8.1% |

15.2% |

10.5% |

|

Town of Corte Madera |

7.7% |

7.8% |

8.5% |

8.4% |

11.0% |

|

Town of Fairfax* |

N/A |

13.9% |

9.8% |

10.5% |

9.8% |

|

Town of Ross |

14.5% |

2.2% |

3.9% |

7.2% |

13.0% |

|

Town of San Anselmo |

2.4% |

1.9% |

2.5% |

4.3% |

7.2% |

|

Town of Tiburon |

6.6% |

3.8% |

4.1% |

4.7% |

5.8% |

|

Total |

8.8% |

7.9% |

8.9% |

13.6% |

10.7% |

| |

< 5% |

|

5% - 10% |

|

10% - 15% |

|

> 15% |

In FY 2016, the City of San Rafael and the Town of Ross had the highest

contribution percentages, 19.2% and 14.5% respectively. The City of San

Rafael’s contribution rate has been consistently high for the last five

years. MCERA, San Rafael’s pension administrator, projects that

contributions will remain high with only a slight decline over the next 15

years.29

In contrast, the Town of Ross had a relatively low contribution percentage

through FY 2014 & FY 2015. The contribution rate would have remained low

in FY 2016 but for a $1 million voluntary contribution to pay down its NPL.

Nevertheless, the Town’s pension administrator (CalPERS), projects that

pension contributions will rise sharply from FY 2014/FY 2015 levels over

the next five years.30

29 “Actuarial Valuation Report as of June 30, 2016.”

Marin County Employees’ Retirement Association. p.15.

30 “Annual Valuation Report as of June 30, 2015.”

California Public Employees’ Retirement System. Reports

for Town of Ross - Miscellaneous Plan, Town of Ross - Miscellaneous Second

Tier Plan, Town of Ross - PEPRA Miscellaneous Plan & Town of Ross - Safety

Plan

Although Fairfax has not yet produced an audit report for FY 2016, we

expect its required contributions will experience an increase over the

next four to five years after which they are projected to decline somewhat

over the following decade.31

Belvedere and San Anselmo had the lowest contribution percentages of 4.2%

and 2.4% respectively.

Examining NPL as a percentage of cash (see Appendix E), Tiburon and Ross

were in the best position, with Tiburon having 25.2% of NPL to cash and

Ross having 33.7% of NPL to cash. The Grand Jury recommends that cash-rich

agencies evaluate their reserve policies and discuss whether a

contribution to pay down the NPL (as Ross did in FY 2016), should be

prioritized. Conversely, San Rafael and Fairfax (based on FY 2015) are

also in the worst position based on our balance sheet metric with a NPL

that is more than double both municipalities’ respective cash positions.

The County is in a strong financial position, spending 7.9% of its

revenues on pension contributions. The County of Marin’s balance sheet has

assets of nearly $2 billion, yearly revenues of over $600 million and cash

of over $400 million. When viewed in the context of its ample financial

resources, the County does not currently appear to be financially strained

by its pension obligations. Furthermore, the county’s significant assets

and ample cash cushion should protect it from further pressure caused by

increasing pension contributions. In 2013, the County made a significant

extra contribution ($30 million) to pay down its NPL and could do the same

in future years to offset increasing contribution requirements from MCERA.

Special

Districts

The Special Districts illustrate the stark differences among agencies. The

safety districts (police and fire), out of all the agencies, spent the

highest percentage of their revenues on pension contributions. The primary

reason that safety agencies have high pension expenses relative to other

agencies is that they are inherently labor intensive, with some of the

most highly compensated public employees with the highest pension benefits

(in terms of percentage of compensation for each year of service) and the

earliest retirement ages. Other than some equipment, such as a fire

engine, the bulk of the revenues are spent on employee compensation and

benefits.

31 “Annual Valuation Report as of June 30, 2015.”

California Public Employees’ Retirement System. Reports

for Town of Fairfax - Miscellaneous First Tier Plan, Town of Fairfax -

Miscellaneous Second Tier Plan, Town of

Fairfax - PEPRA Miscellaneous Plan, Town of

Fairfax - PEPRA Safety Plan, Town of Fairfax - Safety First Tier Plan &

Town of Fairfax - Safety Second Tier Plan

|

Safety District |

FY 2016 |

FY 2015 |

FY 2014 |

FY 2013 |

FY 2012 |

|

Central Marin Police Authority* |

N/A |

13.4% |

20.1% |

17.7% |

16.8% |

|

Kentfield Fire Protection District |

19.0% |

16.7% |

14.7% |

16.9% |

17.5% |

|

Novato Fire Protection District |

17.4% |

18.2% |

17.5% |

18.1% |

19.1% |

|

Ross Valley Fire Department |

11.7% |

10.9% |

9.1% |

16.3% |

61.8% |

|

Southern Marin Fire Protection District |

13.9% |

5.4% |

12.6% |

13.8% |

13.9% |

|

Tiburon Fire Protection District |

20.5% |

31.0% |

14.2% |

14.2% |

15.8% |

|

Total |

16.2% |

15.2% |

15.5% |

16.5% |

22.2% |

| |

< 5% |

|

5% - 10% |

|

10% - 15% |

|

> 15% |

The highest pension to revenue rates were in the Tiburon, Kentfield and

Novato fire districts, which each spent more than 17% of their revenues on

pension payments in FY 2016. Using the metric of NPL to cash on the

balance sheet, the Ross Valley Fire Department had the highest ratio of

nearly 600% (see Appendix E). However, Ross Valley Fire spent only 11.7%

of its revenues on pension contributions in 2016.

The ratios for Tiburon Fire in FY 2015 and FY 2016 are inflated by the

voluntary contributions it made, totaling approximately $2 million over

those two years.

Sanitary districts as a group appeared to be in the best financial

condition based on both balance sheet and income statement data. Sanitary

districts tend to have few employees and own significant assets that

require capital investments to maintain. A capital-intensive business

requires cash, but not many employees. Consequently, their pension plans

appear not to be a financial burden on the agencies.

|

Utility District |

FY2016 |

FY2015 |

FY2014 |

FY2013 |

FY2012 |

|

Central Marin Sanitation Agency |

5.5% |

13.0% |

16.6% |

7.6% |

7.4% |

|

Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District |

2.3% |

2.3% |

2.3% |

3.6% |

3.5% |

|

Marin Municipal Water District |

9.2% |

7.5% |

6.5% |

5.7% |

6.4% |

|

Marin/Sonoma Mosquito & Vector Control |

11.2% |

10.2% |

11.0% |

11.2% |

24.0% |

|

Marinwood Community Services District |

5.5% |

5.2% |

8.0% |

8.7% |

10.7% |

|

North Marin Water District |

4.6% |

3.6% |

3.9% |

8.6% |

6.5% |

|

Novato Sanitary District |

1.5% |

0.9% |

1.4% |

1.8% |

1.3% |

|

Richardson Bay Sanitary District |

2.6% |

2.4% |

3.2% |

2.3% |

2.3% |

|

Ross Valley Sanitary District |

2.3% |

2.0% |

3.8% |

3.8% |

3.2% |

|

Sanitary District # 5 Tiburon-Belvedere |

28.4% |

25.3% |

2.9% |

3.5% |

4.9% |

|

Sausalito Marin City Sanitation District |

3.3% |

4.0% |

3.4% |

2.4% |

5.0% |

|

Tamalpais Community Services District |

5.9% |

5.9% |

6.4% |

5.8% |

5.1% |

|

Total |

6.5% |

6.4% |

6.0% |

5.5% |

6.1% |

| |

< 5% |

|

5% - 10% |

|

10% - 15% |

|

> 15% |

Sanitary District #5 had a very high level of pension contributions at

over 25% for each of the two most recent years. However, this is the

result of large voluntary contributions. Further, the district had cash

equal to three times its NPL. The Novato Sanitary District stood out as

being in particularly good financial condition in that it spends less than

2% of its revenues on pension contributions and has a NPL that is 18% of

its cash position.

The real question for Marin County taxpayers is not whether we are in dire

straits because of pensions — for now, most of the agencies appear to be

able to meet their pension obligations — but which services are going to

be squeezed, which roads aren’t going to be paved, which buildings aren’t

going to be updated because of growing pension contribution requirements.

Alternatively, how many more parcel taxes, sales tax increases and fee

hikes will be required because pension contributions continue to spiral

upwards? In the next section, we will discuss possible alternatives to the

current system of retiree pay.

The Exit

Doors Are Locked

In 2011, Governor Jerry Brown announced a 12-point plan for pension

reform. This plan included raising the retirement age for new employees,

increasing employee contribution rates, eliminating “spiking” (where an

employee uses special bonuses, unused vacation time and other pay

perquisites to increase artificially the compensation used to calculate

their future retirement benefit) and prohibiting retroactive pension

increases. Most of these proposals were incorporated

into the Public Employees Pension Reform Act of 2013 (PEPRA).32 One that was not was Governor Brown’s proposal for

“hybrid” plans for new employees.

The hybrid

proposal consisted of three components:

-

New employees would be offered pensions but

with reduced benefits requiring lower contributions by both employer and

employee.

-

New employees would also be offered defined

contribution plans.

-

Most new employees would be eligible for

Social Security. (Currently, employees not eligible for CalPERS or

CalSTRS -- generally, part-time, seasonal and temporary employees -- are

covered by Social Security.)

The Governor’s proposal was for each of these three components to make up

approximately equal parts of retirement income. (For those not eligible

for Social Security, the pension would provide two-thirds and the defined

contribution plan one-third.)

It may be helpful at this point to pause and define our terms. A

traditional pension — like the plans covering public employees in Marin —

is a defined benefit (DB) plan. Under a DB plan, the employee is

eligible for a pension that pays a defined amount, typically a formula

based on retirement age, years of service and average compensation.

Because the benefit is defined, the contributions by employer and employee

will be uncertain; they, along with the investment returns on the

contributed assets, must be sufficient to fund the defined benefit.

Under a defined contribution (DC) plan, such as a 401(k), both

employer and employee make an annual contribution. Typically, the employee

chooses a portion of pre-tax salary that is contributed to the plan and

the employer matches a percentage of the employee’s contribution. The

funds are placed in an investment account and the employee chooses how the

funds are invested (usually from a range of choices established by the

employer). What is undefined is the value of the account at the time the

employee retires as this depends upon the total of contributions and the

rates of return over the life of the account. By law, 401(k) plans are

“portable”; they permit the employee to move the account to an Individual

Retirement Account (IRA) should he/she change employers.

The primary difference between DB and DC plans is who assumes the risk of

lower investment returns and greater longevity. In a DB plan, it is the

employer; in a DC plan, it is the employee. Furthermore, a DB plan poses

some risk to the employee: If the employer does not make the required

contributions, the pension administrator will be required to reduce

pension benefits to the retirees of the employer. In November 2016,

CalPERS announced that it would cut benefits for the first time in its

history. Loyalton, California was declared in default by CalPERS after

failing to make required contributions towards its pension plans. The

CalPERS board voted to

32 “Twelve Point Pension Reform

Plan.” Governor of the State of California. 27 Oct. 2011.

reduce benefits to Loyalton retirees.33 More

recently, in March of 2017, CalPERS voted again to cut benefits for

retirees of the East San Gabriel Valley Human Services Agency when it

began missing required payments in 2015.34

Over the past several decades, private industry in the US has moved

decidedly toward DC and away from DB. In 1980, 83% of employees in private

industry were eligible for a DB plan (either alone or in combination with

a DC plan).35 By March 2016, the Bureau of Labor

Statistics reported that among workers in private industry, 62% had access

to a DC plan while only 18%

had access

to a DB plan. This compares with workers in state and local government,

where 85% had access to DB plans and 33% to DC plans (some workers are

eligible for both).36

Eliminating the risk of an underfunded plan is the primary reason that

private employers have been moving away from DB plans, but there are

several others. In a traditional DB plan, the employer is responsible for

managing the assets held in trust for future retirees. This leads to costs

for both investment management and oversight of their fiduciary duties. In

addition, as the economy has shifted from manufacturing toward service and

high technology, new firms have sprung up that did not have unionized work

forces or legacy DB plans and chose the simplicity

and lack

of risk of DC. The shift from DB to DC may also reflect the preference of

younger employees for the portability and transparency of DC.37

In public employment, which has fewer competitive pressures and a higher

percentage of workers represented by unions, these same trends have not

occurred, leaving more DB plans in place.

Under PEPRA, new employees hired after January 1, 2013 are still eligible

for DB plans, but at a lower percentage of average compensation and a

later retirement age (generally two years later). These important steps

reduced the annual cost of employee pensions but still leave the employer

with the administrative cost and fiduciary duty. While PEPRA prohibits

retroactive increases, which prevents the state from making the same

mistake it made in the late 1990’s, investment performance that is

significantly below target could again produce a large unfunded liability.

It is argued by some38 that everyone would

benefit from a more secure retirement; rather than taking DB plans away

from public employees, they should be made available to all workers.

33 “CalPERS Finds the City of

Loyalton in Default for Non-Payment of Pension Obligation.”

CalPERS.ca.gov 16 November, 2016.

34 Dang, Sheila “CalPERS Cuts

Pension Benefits for East San Gabriel Valley Human Services.”

Institutionalinvestor.com 16

March, 2017.

35 “Pensions: 1980 vs. Today.”

New York Times, 3 Sep. 2009

36 “National Compensation

Survey.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, March 2016

37 Barbara A. Butrica and Howard M. Iams and

Karen E. Smith & Eric J. Toder. ”The Disappearing

Defined Benefit Pension and Its Potential Impact

on the Retirement Incomes of Baby Boomers.” Social Security

Bulletin, Vol. 69, No. 3, 2009

38 Aaronson, Mel and March, Sandra and Romain,

Mona. “Everyone Should Have a Defined- Benefit Pension.”

New York Teacher. 17 Feb. 2011.

While this argument has some appeal, it ignores the fact that US commerce

has adopted DC plans as the de facto standard. Further, as DB plans for

public employees exhibit significant unfunded liabilities, it stands to

reason that DB programs for private employees with comparable benefits

would suffer the same financial difficulties.

It is easy to understand why taxpayers, who have to manage the risks of

their own retirements using DC plans, would object to guaranteeing the

retirement income of public employees with DB plans. In a February 2015

nationwide poll, 67% of respondents favored requiring new public employees

to have DC instead of DB plans.39 A California

poll in September 2015 put that number at 70%.40

As noted above, the changes to state retirement law under PEPRA did not

make DC or hybrid plans an option for public employees. While existing DC

plans were grandfathered by PEPRA, any agency proposing to offer a new DC

or hybrid plan in place of an existing DB plan would face a series of

hurdles:

-

According to the County Employees

Retirement Law of 1937, the County of Marin would require specific

legislative approval to amend the law to allow the introduction of a

DC or hybrid DC/DB plan.

-

For other public agencies, PEPRA did not

create any approved DC or hybrid models; although neither did it

explicitly prohibit them. Any changes by agencies that are

participants in CalPERS would require approval of the CalPERS board.

It appears likely that CalPERS would disapprove such a request under

PEPRA section 20502, as an impermissible exclusion of a class of

employees. (Some differentiations — by job classification, for example

— are permissible.)

In addition, negotiations with the relevant collective bargaining unit

would need to take place, a requirement that is made explicit in PEPRA

section 20469.

An additional obstacle is termination fees. If a CalPERS participating

agency chooses to terminate its DB plan, it must make a payment to

CalPERS to satisfy any unfunded liability. This fee would be

calculated by discounting the liability using a risk-free rate (see

Glossary for definition), which might be four to five percentage

points lower than the rate normally used to calculate the NPL.

The actual calculation of the termination liability is done at the

time of the termination, but in its annual actuarial valuation reports

CalPERS provides two estimates intended to describe the range in which

the liability is likely to fall. While CalPERS has used a 7.50%

discount rate to calculate NPL for active plans, it uses a combination

of the yields on 10-year and 30-year

39 “Pension Poll 2015

Topline Result,” Reason-Rupe Public Opinion Survey, 6

February 2015

40 “Californians and Their

Government,” Public Policy Institute of California Statewide

Survey, September 2015

Treasury securities — which respectively yield 2.19% and 3.02% as this

report is written — to calculate the termination liability. In its

most recent actuarial reports, it provided estimates of agencies’

termination liability using discount rates of 2.00% and 3.25%. To

illustrate, at June 30, 2015 (reports for fiscal 2016 were not yet

available as this was written), the City of Larkspur had a NPL of just

over $9 million, but Larkspur’s termination liability was estimated at

between

$46.8 million and $64.1 million, or between five and seven times its

NPL. This range is very typical.

Here, again, we should define our terms. When a pension plan is

terminated, the claims of all eligible participants are satisfied,

either through a lump-sum payment or through the purchase by the plan

of annuities that pay all benefits to which the participants are

entitled. The plan is then liquidated; no further benefits accrue to

employees and retirees and no further contributions are required from

the employer.

A pension plan freeze is different from a termination. A plan can be

frozen in a variety of ways. A plan might terminate all future

activity so that any benefits earned prior to the freeze are still due

but no further benefits are earned by any employees. Alternatively, a

pension plan might choose to keep all terms in place — including

benefit accruals for future service and required future contributions

— for existing employees and retirees but enroll all new hires in DC

plans. Other variations are possible.

Currently, CalPERS does not distinguish between a termination and a

freeze. If an employer were to propose converting new employees to a

DC plan, CalPERS would treat it as a termination because it is

impermissible for a CalPERS plan to differentiate between groups of

employees on the basis of when they were hired.

Absent legislative action, an agency that wanted to freeze its current

DB plan and make all new employees eligible for a DC-only or hybrid

plan would make an application to CalPERS. The CalPERS board would

conclude that excluding employees from the existing DB plan on this

basis was impermissible and declare the plan terminated, triggering

the imposition of a fee five to seven times the amount of the NPL. For

an agency that wishes to take better control of its financial

position, this would be a counter-productive endeavor.

CONCLUSION

The net pension liability of Marin’s public agencies cannot be made to

disappear. It represents benefits earned over several decades by

public employees and constitutes a legal and ethical obligation. Some

progress has been made to reduce growing liabilities (such as PEPRA’s

anti-

spiking provisions, which are the subject of a lawsuit currently under

appeal at the state Supreme Court).41

However, the vast bulk of this liability will need to be paid.

The recommendations proposed by the Grand Jury are intended to achieve

three objectives:

-

Avoid further increasing the pension

liabilities of Marin’s public agencies by shifting from DB to

DC-only and/or hybrid retirement plans.

-

Increase the rigor and extend the

planning horizon of fiscal management by Marin’s public agencies.

-

Improve the depth and quality of

information provided to the public.

In the course of its investigation, the Grand Jury found two models

that may help achieve these objectives, one from right next door and

one from across the country.

In September 2015, Sonoma County empanelled the Independent Citizens

Advisory Committee on Pension Matters consisting of seven members,

“none of whom are members or beneficiaries of the County pension

system.”42 The panel conducted an

investigation and published in June 2016 a comprehensive and highly

readable report with recommendations for containing pension costs,

public reporting and improving fiscal management.43

In 2012, New York State Office of the State Controller introduced a

Fiscal Monitoring System, which is intended to be an early-warning

system for financial stress among the state’s municipalities and

school districts. It takes financial data from reports filed by the

agencies and economic and demographic data to produce scores to

identify fiscal stress. The OSC also offers advisory services to

assist those agencies in developing plans to alleviate their financial

stress.44

We believe that these two models could be helpful as Marin’s public

agencies come to terms with the fiscal realities of the years ahead.

One final point: As bad as this report may make things look, they will

almost certainly look worse in the next few years because of the

lowering of discount rates by pension administrators. We believe that

these actions by CalPERS, CalSTRS and MCERA are well founded and

prudent, but they will result in increases to the NPLs of every

agency, necessitating higher payments in

41 Marin Association of Public Employees v. Marin

County Employees Retirement Association

42 “Independent Citizens’s

Advisory Committee on Pension Matters.” County of Sonoma.

43 “Report of Independent Citizens Advisory

Committee on Pension Matters.” County of Sonoma. June 2016.

44 “Three Years of the Fiscal Stress Monitoring

System,” New York State Office of the State Controller, September 2015

the near term to amortize the higher NPLs. The result will be that

budgets, already under pressure, will be squeezed further.

FINDINGS

F1. All of the agencies investigated in this report had pension

liabilities in excess of pension assets as of FY 2016.

F2. A prolonged period of declining global investment returns has led

pension plan assets to underperform their targeted expected returns.

F3. MCERA, CalPERS and CalSTRS have lowered their discount rates,

which will result in significantly higher required contributions by

Marin County agencies in the next few years.

F4. If pension plan administrators discounted net pension liabilities

according to accounting rules used for the private sector, increases

in required contributions would be vastly larger than those required

by the recent lowering of discount rates.

F5. Most Marin County school districts have a negative net position

due in part to the addition of net pension liabilities to their

balance sheets.

F6. The required contributions of Marin school districts to CalSTRS

and CalPERS will nearly double within the next five to six years due

to legislatively (CalSTRS) and administratively (CalPERS) mandated

contribution increases.

F7. Pension contribution increases will strain Marin County agency

budgets, requiring either cutbacks in services, new sources of revenue

or both.

F8. The private sector has largely moved away from defined benefit

plans primarily due to the risk of underfunding, offering instead

defined contribution plans to its employees.

F9.

Taxpayers bear most of the risk of Marin County employee pension plan

assets underperforming their expected targets.